|

|

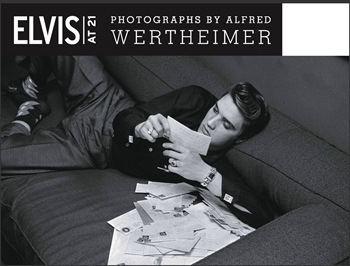

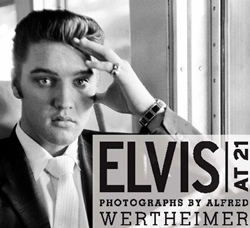

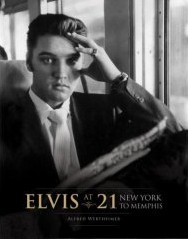

All images in this article are © Copyright Alfred Wertheimer and come from the exhibtion and his excellent book "Elvis At 21" - and are displayed here low-resolution. See details of how to buy this fabulous book below.

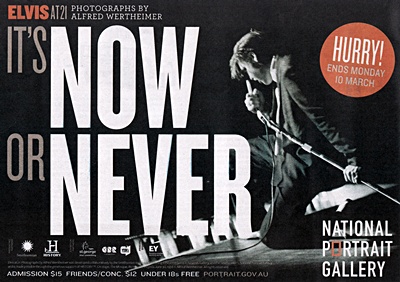

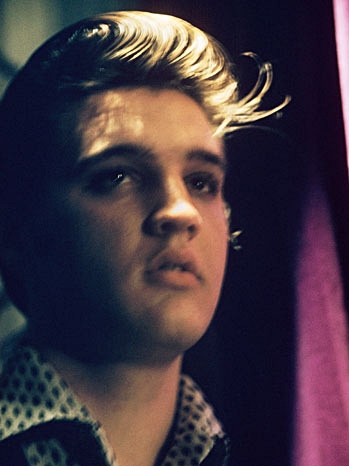

''Elvis who?'' was Alfred Wertheimer's reply, when asked by record company RCA to shoot publicity photographs of its new signing. On March 17, 1956, Wertheimer turned up at CBS Studios, where Elvis would be making a guest appearance on the Dorsey Brothers Stage Show. Three months later, Wertheimer would photograph the rising star in a foolish segment of the Steve Allen Show. After this, he was hooked and decided to follow Elvis as a freelance photojournalist. The pictures, produced by no more than a week's shooting, between March and July 1956, remain the most intimate and revealing images of a career that would last another 21 years and a legend that has never faded. The exhibition, Elvis at 21, at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, must have been on the itinerary for many of the diehard fans who make their way to Parkes every year for the annual Elvis Presley Festival, held to coincide with the singer's birthday on January 8. For the hundreds who attend in full regalia, the most popular choice of costume is the white satin jumpsuit Elvis wore in a televised concert of 1973. Elvis had been squeezing himself into these of-the-time camp outfits since his comeback season in Las Vegas in 1969. Although he still managed a few memorable tunes, during the very last couple of years of his life, Elvis seem to become a caricature of himself, and a tragic figure. The ultimate insult was the claim that he had turned into Liberace.

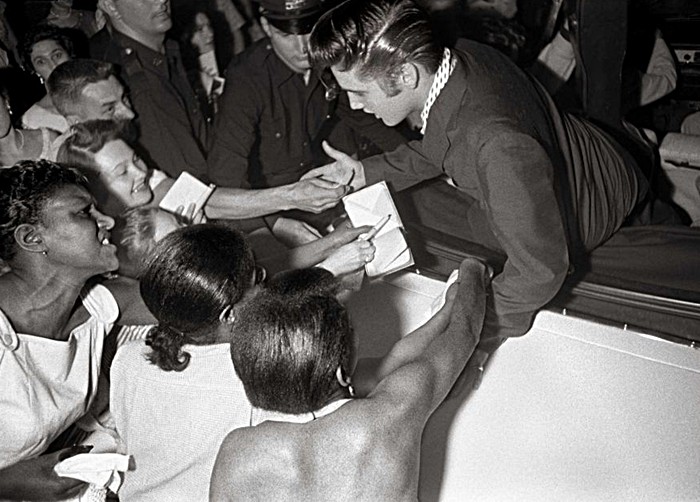

When he died in 1977, at the age of 42, Elvis was using so many prescription drugs supplied by various doctors that some said it was a miracle he had survived as long as he had. His reputation had already suffered a mortal blow during the 1960s when his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, signed a series of contracts that condemned Elvis to make a series of increasingly lame movies, padded with insipid pop songs. The comeback was a way of dragging Elvis out of the pit into which Parker had consigned him. None of this terrible decline, described in detail by biographers such as Peter Guralnick and Jerry Hopkins, could be predicted from Wertheimer's photographs of the 21-year-old Elvis in his first year of stardom. Instead, we see many of the positive aspects of his personality: his charm, his politeness, his musicianship and his perfectionism. The young Elvis has a charisma that shines out from these photos. It is as if we can travel back in time to recapture the excitement of those first appearances that drove fans into a screaming frenzy. Wertheimer has said the key to these photographs is that Elvis ''permitted closeness''. It was a brief window of opportunity at this early stage of his career, because such closeness would soon be impossible.

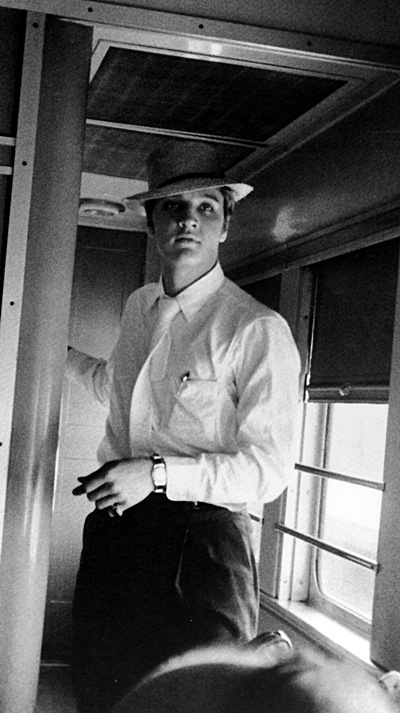

In 1956, the young Elvis could walk down the street or sit on a train without anyone recognising him. He could pick up a girl in a diner and kiss her in a corridor, with only Wertheimer watching. It wasn't that Elvis expressly permitted the photographer to record such intimate moments. It was a matter of indifference whether the camera was there or not. The word ''paparazzi'' would not enter the international vocabulary until Fellini's film, La Dolce Vita, was released in 1960, perhaps not until Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton arrived in Rome to make Cleopatra three years later. In 1956, a star could still have a private life in a way that is unimaginable today, when high prices are paid for shots of celebrities looking ugly or cheating on their spouses.

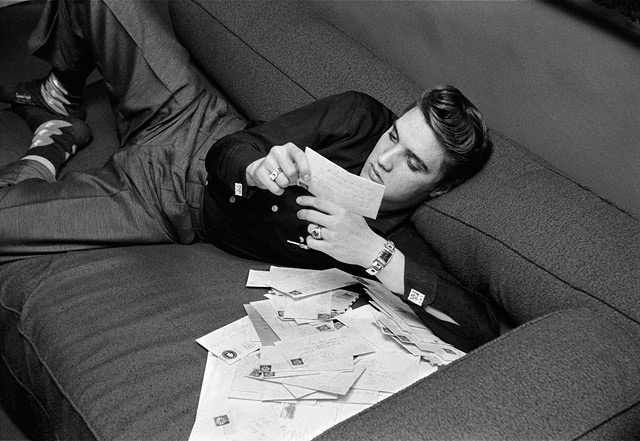

In Wertheimer's candid photos, we see Elvis dozing on a couch surrounded by a mountain of fan mail, reading an Archie comic on the train, buying his lunch on a railway station platform, greeting a small group of admirers at the stage door, horsing around in a swimming pool, and so on. There is nothing intrinsically remarkable in any of these scenarios and nothing aesthetically remarkable about Wertheimer's technique. The one fact is Elvis himself. On the verge of becoming the most famous man in the US, he acts, off stage, in a way that is natural and unaffected. In a very short time, he would be barricaded behind the walls of Graceland, which he would buy in 1957. His every public appearance would become a media event. In June 1956, Elvis had already caused a sensation by gyrating his hips on the Milton Berle Show. Newspaper critics and letter writers denounced the ''obscenity'' of the performance. The director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, opened an FBI file on the singer after receiving a report from the Army Intelligence Service claiming Elvis was ''a definite danger to the security of the United States'', because of his ability ''to rouse the sexual passions of teenaged youth''. The television compere Steve Allen, who detested the rock 'n' roll craze, set out to bring Elvis down to earth, with two ridiculous segments in his July 1 program. In one, Elvis had to dress like a cowboy and be introduced as ''Tumbleweed Presley'', while in the other he was obliged to sing Hound Dog to a real basset hound that sat impassively on a plinth, with a top hat attached to its head.

Wertheimer captures these demeaning scenarios that Elvis endured with good humour. The fans, however, were outraged. Three days later, he was back in Memphis for a concert at the local baseball stadium, Russwood Park. Conscious of the buffoonery of his TV appearance, he told a full house of 14,000: ''Tonight you're going to see what the real Elvis is all about!''

That concert is recorded in Wertheimer's photos, the most memorable image being a sweeping shot of the audience. Wide-eyed young women, men in sailor suits, open mouths, horn-rimmed glasses - every face is a study in awe, expectancy and desire. This picture might be set alongside a sequence in which Elvis has a tete-a-tete in the street with a bespectacled young woman, conservatively dressed in a white skirt with matching hat and gloves. When he whispers something and leaves, she breaks down in tears.

Then there is the iconic photo reproduced on the cover of Peter Guralnick's 1994 book, Last Train to Memphis, in which Elvis sits alone at the piano singing gospel songs after arriving early for a rehearsal. There are traces of ''the real Elvis'' in each of these pictures. His on-stage presence was electrifying, but with a fan in the street, he was all charm and modesty. Sitting at the piano, we see the serious, reflective musician, who would demand one take after another until he was satisfied with a recording. This professionalism wasn't obvious to his detractors and he would occasionally play up to expectations. He would dress in the brightest colours and make love to the microphone. He was deathly pale and wore eyeshadow. One fan in a vox pop said: ''I like him because he's so mean.'' When a journalist quizzed him about his accomplishments, Elvis replied: ''In my kind of music, you just get out there and go crazy.'' It was all a game and a pose. The Elvis in these photographs is anything but crazy. One sees an artist with the profile of a Greek statue and the same kind of clothes as those worn by the black performers. He had a fierce commitment to the music and took all the distractions of fame in his stride, because they had yet to become a burden. Elvis was enjoying himself in a way that would seem like a distant dream 10 years later, when he was churning out three turkeys a year for Hollywood.

One of the crucial points of the ‘Elvis At 21’ exhibition is how it clearly explains the historical setting of this week in Elvis’ life in post-war America. Issues of racism, segregation and the impact that Elvis’ power would have to motivate the teenagers of the time are obviously shown. In a disarmingly casual sequence, Wertheimer shows Elvis getting off the train before the scheduled stop in Memphis, to walk home. The station is called White, which is an ironic destination for a southern singer who made black music acceptable to a white audience. Elvis walks to the footpath, asks for directions, then turns and waves to the conductor, before setting off to join his parents. It must have been one of the last occasions he was able stroll through the streets like a mere mortal. By John McDonald (with added input from EIN)

To read the SHM on-line article go here. EIN presentation & Edit by Piers Beagley. Click to comment on this article

EIN Website content © Copyright the Elvis Information Network.

Elvis Presley, Elvis and Graceland are trademarks of Elvis Presley Enterprises. The Elvis Information Network has been running since 1986 and is an EPE officially recognised Elvis fan club.

|

|