|

|

An exhibition in Paris about the birth of rock’n’roll shows how music learnt to march to a new beat after the second world warSource: The Sunday Times, 1 July 2007

Sometimes it is the smaller juxtapositions that catch your eye. At the Fondation Cartier’s new exhibition, you can read a report from Variety, dated March 28, 1957, describing a “rock’n’roll riot” at no less a setting than the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The city council, the paper declared, had placed a ban on any future “record hops”. On the same page, lower down, is an item announcing Louis Armstrong’s plans to tour the UK.

Not the two most earth-shattering pieces of news, perhaps, but the articles hint at a transitional moment in pop culture. As late as 1957, a jazz musician’s itinerary was still something for industry insiders to talk about. Yet everyone was all too aware that a restive child had come crashing through the window. Teenagers had, of course, been around since well before the 1950s, but the Eisenhower era saw them asserting their values and spending power as never before. And, as the extracts from teen magazines show, they had their own distinct slang: cuttings (records), chlorophyll George (a one-dollar bill), draggin waggin (a car), double-dome (“a real square”). The collision between adult and adolescent taste is a central theme in the show, which has just opened at the chic Left Bank art establishment, an institution usually more concerned with championing modern art than singing the praises of Buddy Holly. Rock’n’Roll 39-59 evokes an age of innocence – the memorabilia, screen footage and record sleeves documenting a period when a wave of youthful energy transformed the face of our culture. Not everyone was impressed at the time, of course. The exhibition catalogue, a stylish blend of journalism and entertainment, includes an oft-quoted remark by Frank Sinatra: “Rock’n’roll smells phony and false. It is sung, played and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic reiteration, and sly, lewd, in plain fact dirty lyrics ... it manages to be the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth.” Half a century later, the fruits of a postwar consumer society have been reverently repackaged. Turn left past the entrance, and you are confronted by a 1953 Cadillac. Behind it, arrayed on the walls, one above the other, is a swarm of juke-boxes. And on a wall nearby – displayed with all the solemnity of a religious relic – is the jacket that Elvis Presley wore for his final appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Walk into the recreation of a recording studio and you can imagine yourself back at the moment the pioneers took their first halting steps towards the hall of fame. To be frank, in terms of sheer scale, the exhibition doesn’t quite live up to expectations, and some of the archive material will be overly familiar to anyone above the age of, say, 30. But there are enough incidental pleasures to keep a music-lover occupied. It goes without saying that Elvis is the pivotal figure – the event, after all, coincides with the 30th anniversary of his death. Magazines devoted to every twist and turn of his personal life tell their own story on the covers: Elvis Presley: Hero or Heel?, How Elvis Looks in Uniform, How It Feels to Be Elvis. How quaint it all looks in the light of our remorseless modern-day celebrity industry.

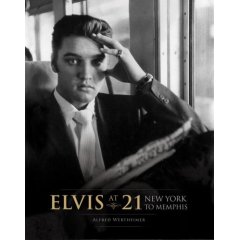

Most potent of all is the celebrated sequence of photographs by Alfred Wertheimer, taken in 1956, when the young singer was on the cusp of superstardom. Wertheimer knew next to nothing about the newcomer or his music when he was given the assignment of following him around in the recording studio, on the road or trying out his romantic patter on a female fan in a diner. As a result, perhaps, the photos still seem astonishingly fresh and unselfconscious. The most memorable image of all – and the most poignant, too – shows Presley jumping off a train at a small station near his home. One frame captures him asking a black woman for directions. Then he walks away, after a final boyish wave to the camera. As Wertheimer recalls: “That was probably one of the last times he could just walk down the street like an ordinary guy.” The show’s handsome 420-page catalogue deserves to become a collector’s item. Where the exhibition floors feel underpopulated in places, the book brings the subject into dramatic focus, the illustrations, publicity stills and posters interspersed with weighty extracts from the work of writers as distinguished as the late David Halberstam. Our own Charlie Gillett – in an extract from his atmospheric book The Sound of the City – crisply delineates the main musical currents that led to the rise of the new youth music. Peter Guralnick adds elegant thumbnail sketches of taste-makers such as the iconoclastic DJ Dewey Phillips. Greil Marcus rounds it all off with his selection of the seven records that defined the period. (He starts with Fats Domino’s The Fat Man and ends with the ultra-romantic harmonies of the Fleetwoods’ Come Softly to Me.) It is the sense of historical perspective that redeems the show as a whole. Some discussions of rock’n’roll treat the music that came before it as a mere distraction, to be glossed over as briskly as possible. (Note the way that black music of the prerap era tends to be shoved aside whenever newspapers organise those “greatest records of all time” lists.) By adopting a more generous timescale, pegged to the outbreak of the second world war, the curators give themselves ample room to explore the trends in blues, R&B and country that set the stage for Jerry Lee Lewis et al. Archive photography from the days of Jim Crow’s segregation enhances the sense of bloodlines ebbing and flowing. In that respect, nothing is quite as eloquent as the sign on the picture from the Memphis of yesteryear: “No white people allowed in zoo today.” As for the cutoff point, 1959, it feels absolutely natural. Elvis had been drafted into the army by then; and, even though the record companies continued to market hits, the spirit had changed irrevocably. A new decade and a new age were about to begin. Sometimes the exhibition’s approach is slightly too austere. One or two of the displays break down into long lists of vintage names that will defeat all but the hardiest of music geeks. But there are neat touches elsewhere. My favourite exhibit – Les Origines du Rock’n’Roll – combines a map of the USA with a network of earphone sockets that allows visitors to listen to the trademark songs of any given locale. Any chance to hear the rumbling New Orleans piano of Professor Longhair should be seized with both hands. Moreover, it is good to see jazz brought into the picture. It is sometimes tempting to assume that the great musicians from that particular school operated in a lofty realm far from the commercial arena. Yet it takes only a moment to realise how thoroughly band leaders such as Count Basie and Lionel Hampton were immersed in the blues. Louis Jordan, of course, created his own dynamic fusion of R&B and jazz. Nat King Cole was singing Route 66 long before the rockers came into view, while James Brown’s version of Night Train can trace its ancestry back at least as far as Duke Ellington’s Happy-Go-Lucky Local. What the show does not address is the question of how much was lost due to the seismic shift from adult to teen values. But that is, perhaps, a question for another day, another exhibition. Rock’n’Roll 39-59, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 261 Boulevard Raspail, Paris, until October 28; www.fondation.cartier.com

|

|