Back in 1956 while "Elvis-mania" was raging around the world, Freddy Bienstock joined the New York division of Hill & Range, Elvis' publishing company, as a song plugger.

Enlisted by his cousins, Jean and Julian Aberbach who headed the operation, Freddy worked hand in hand with Elvis providing him with a parcel of songs to record.

While Elvis ultimately made the final decision on the songs he chose, Freddy was his musical lifeline and Elvis' "ears."

Throughout Elvis' career, as the liaison between scores of Hill & Range songwriters, outside songwriters and the King himself, Freddy was perpetually seeking quality material suited for his star client.

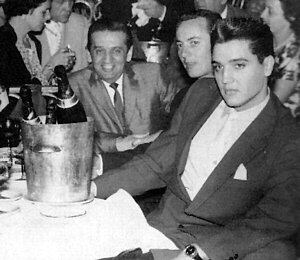

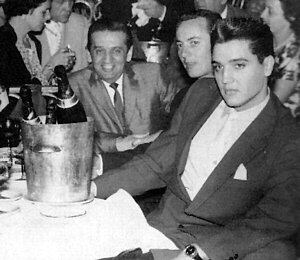

(Right:Freddie Bienstock and Elvis in Paris)

|

|

September 20th 2009: Freddy Bienstock, Who Published Elvis Presley Hits, Dies at 86:

Freddy Bienstock, a prominent music publishing executive who had a long association with Elvis Presley as his designated song screener, died on September 20th 2009 at his home in Manhattan. He was 86. His death was announced by his company, Carlin America.

Born in Switzerland and reared in Vienna, Mr. Bienstock and his family, who were Jewish, fled to the United States in 1939 and settled in New Jersey. Upon visiting a cousin who worked as a Brill Building song plugger — pitching new material to bandleaders and singers — a star-struck young Mr. Bienstock decided to go into music publishing.

At age 14 he got a job as a stockroom clerk at Chappell Music and was soon plugging songs himself, turning to R&B music as the big-band era faded. By the mid-1950s he was working for his cousins Jean and Julian Aberbach, whose company Hill & Range had become the dominant publisher of country music. Like them, Mr. Bienstock had a strong Continental accent and cut an unusually debonair figure for the pop-music business, wearing monogrammed shirts and carrying a monocle on a silk cord.

Hill & Range’s most promising client was Presley, and Mr. Bienstock was assigned to find him material. Songwriters, eager to be recorded, urgently satisfied Mr. Bienstock’s every request, said Jerry Leiber, who with Mike Stoller wrote songs like “Jailhouse Rock” and “Don’t” that became hits for Presley.

“He’d say, ‘I need a Christmas song, guys,’ ” Mr. Leiber said of Mr. Bienstock in a telephone interview on Wednesday. “‘Get it to me tomorrow morning; I don’t care how good it is.’ So Mike and I would stay up all night and write it.”

It was also Mr. Bienstock’s job to maximize income for his employer, and songwriters were often pressured to forfeit a large portion of their royalties to Hill & Range and Presley, a cut that Alex Halberstadt called “the Elvis tax” in “Lonely Avenue,” his biography of the songwriter Doc Pomus.

During the 1960s Mr. Bienstock was charged with finding songs for Prelsey’s many films. The pace of production — Presley was making three or four pictures a year, each with 10 or more new songs — wore down any quality control, he said in Ken Emerson’s book “Always Magic in the Air: The Bomp and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era.”

“It was not the best material after a while,” he said.

In 1966 Mr. Bienstock bought Hill & Range’s British subsidiary, Belinda Music, renaming it Carlin Music after his daughter, Caroline, and he began making numerous publishing acquisitions.

Far too many of Elvis' associates are leaving this mortal coil. Ken Sharp was very pleased that he managed to interview Freddie Bienstock back in 2006 for his book about Elvis' composers 'Writing For The King'.

Below is an edited extract of Ken Sharp's interview with Freddy Bienstock.

Click here for more information about the sensational book 'Writing For The King'.

Ken Sharp: Can you recall the first time you heard about Elvis?

Freddy B: The first time I became aware of Elvis was when Colonel Parker told us about him. I met him and he did The Steve Allen Show in New York. I thought he was quite terrific. Unusual for the day but still very compelling. What made me realize he wasn’t a flash in the pan was seeing the reaction of the teenagers when he did personal appearances. When he did a personal appearance at that time the teenagers used to scream so unbelievably. It was really extraordinary. I felt Elvis would last for a long time. After “Heartbreak Hotel,” we knew Elvis would be a success for years and years.

Ken Sharp: There’s information to indicate that Hill & Range got involved with Elvis much faster than the Colonel and RCA.

Freddy B: Yes, to some extent Hill & Range recognized that Elvis would be very successful before RCA and the Colonel. At that time Hill & Range had a deal with Sam Phillips at Sun Records. We had a publishing deal with him, Hi-Lo Music. We were aware of Elvis from a number of sources. At the time when the Colonel first tipped us off about Elvis at Hill & Range, printed music was the indication of the popularity of an artist. We printed an Elvis Presley folio and there was an absolutely incredible reaction to it. It didn’t sell a fucking copy anywhere except in Memphis and in Texas where it sold by the car load. My cousin, Jean, said to me, “He comes from Memphis so that’s why it sold well there” but we couldn’t figure out what happened in Texas. Then we found out that he did some personal appearances in Texas. That really tipped us off that wherever Elvis appeared he was going to sell very well. His popularity really grew as he did tours and was exposed on TV shows like The Ed Sullivan Show and The Tommy Dorsey Show. That really did it for him.

Ken Sharp: Characterize your day to day role with Elvis as a song plugger.

Freddy B: I first started working with Elvis in 1956 and my first success with him was with “Don’t Be Cruel.” My duties at Hill & Range were primarily to find songs for Elvis and to present them to him before he had a session. I would gather songs by various songwriters and then go down to Memphis and play them for him. Then he’d either accept or reject the songs presented to him. His reaction to the songs was always the same. If he liked it he’d say, “Put it aside, I like it.” He would not go mad over things. If he didn’t like a song he would reject it and say “It’s not for me.”

I remember clearly one time I brought him a Leiber and Stoller song called “Just Tell Her Jim Said Hello,” which I thought was a terrific song. Elvis turned it down. Then about a year later I brought it back to play for him again. He had been listening to hundreds of songs in between and after eight bars he said, “I didn’t like it the first time but let me think about it.” Then he finally did record it but it was not a hit for him, which was a great disappointment. I thought “Just Tell Her Jim Said Hello” was a terrific song. I think we gave it to a black girl to record and she did a very good job, had a very good arrangement but it didn’t make it with her either.

Ken Sharp: What were the ingredients for a song that would work for Elvis?

Freddy B: I can’t describe it exactly. But I just kind of knew from the past what kind of songs Elvis liked and what I thought might capture his attention. I can’t put my finger on any specific ingredients but I’ll try. It was either a terrific melody or a novelty kind of lyric idea like “All Shook Up.” That grabbed him and I knew it would. I also knew he would go for an adaptation of “O Sole Mio.” I had five different teams writing an adaptation. Elvis finally recorded the Aaron Schroeder one and it was an enormous success.

Pomus and Shuman came to me and said, “’It’s Now Or Never’ was such a big hit, why don’t we do an adaptation of ‘Sorrento’?” and I said, “Great!” It was their idea, it wasn’t mine. That turned out to be “Surrender.” But it was my idea to adapt “O Sole Mio” because I knew Elvis liked the song. Elvis was attracted to European melodies.

Ken Sharp: How much of a demo would Elvis have to hear to know whether he wanted to record the song or not?

Freddy B: If Elvis didn’t like a song he’d only play about eight bars and then he would take it off. Then there were times he’d want to hear it again and again. Elvis would often adapt the arrangements inherent in the demos.

Ken Sharp: How many demos would you normally bring to play for Elvis before a session?

Freddy B: A lot. Sometimes I’d go to Graceland and play him the demos. Other times I’d play him the demos in the studio. I’d bring two to three dozen demos. He’d only do 12 songs for an album. He would pick more songs than he’d actually record. Then he would play it at home and play it for his friends to see which ones had the right feel.

Ken Sharp: You’ve said that Elvis had “terrific song sense.”

Freddy B: He knew exactly what he wanted to do. You couldn’t talk Elvis into doing a song. He had to feel it. He knew what would work for him. On songs that he was particularly fond of he would make a real effort, sometimes he’d do 40 takes. He would know what he really wanted. It depended on whether he was sold on the song or not. If it was a song that was not terribly important to him he would just record it three or four times and that was it. But there were songs that he really identified with and those were the ones that he put a lot of work into. I remember he liked “The Girl Of My Best Friend” a lot and he did many takes on that. When there was a song he especially liked he was almost a perfectionist about getting it just right.

Elvis had complete freedom in the studio. He would listen to various takes over and over again and he would make the final decision as to what take to use.

Elvis learned the songs on the demos fairly quickly. He was meticulous in terms of the final result. He would listen to takes over and over and over, less so with the movie songs.

Ken Sharp: Were there certain writers Elvis loved that he’d agree to cut their songs without hearing them?

Freddy B: No. He would listen to it. He would always listen. He would not just record a song because a certain writer wrote it. Never. He also liked Don Robertson’s music, which was very country. He recorded a number of his songs but never without hearing them first.

Ken Sharp: Some songwriters hired demo singers who’d try and sing like Elvis while others consciously instructed those who sang their demos not to sing like Presley. In terms of the success ratio of Elvis selecting a song, was one approach more successful than another?

It didn’t matter. It was some writer’s ideas to try to imitate him and flatter him. He cared about the song itself and that’s it.

Ken Sharp: You attended all of Elvis’ recording sessions, what was your role?

Freddy B: At his sessions I’d already seen Elvis and he had already made up his mind of what songs he was going to do and that’s where my role ended. So I just stayed there in case he wanted another song. I did not contribute in the production of the music.

Ken Sharp: I understand there’s a funny story about Jean Aberbach presenting a strange choice of a song for Elvis to record.

Freddy B: We had a recording session in California and Elvis was doing a Christmas song or a religious song. Jean had this song called “Here Comes Peter Cottontail.” I told him I didn’t think it would be for Elvis but he insisted that it would be good for him. He brought in a piece of sheet music and when Elvis was out on a break he put the sheet music on his music stand. (laughs) Elvis came back and looked at it and said, ‘Who brought that B'rer Rabbit shit in here?” (laughs)

Jean left in a hurry and never came back to another session. (laughs) I told Jean that Elvis would not do that song and that it was ridiculous. But he insisted that Elvis would do it. So Jean put it on his stand and hoped he would thank him in appreciation and that didn’t happen. (laughs)

Ken Sharp: Share your memories of visiting Elvis in Paris and Germany while he was stationed in the Army. Was he worried about the state of his career?

Freddy B: In Paris Elvis was primarily interested in having a good time. I didn’t know what to do with him so I decided to take him to this nightclub called The Lido on the Champs Elysées. They had a chorus line of English girls. You wouldn’t believe it. He was there for ten days and he made it with 22 of the 24 girls. (laughs) It was unbelievable. There was one coming in the front and one leaving in the back. The overflow was too hard to handle. (laughs) We didn’t talk much about songs; it was mainly a social visit. Elvis was concerned about his career to some extent. He thought that maybe the fans would forget him or be less enthusiastic about him. What helped keep the fans’ interest were the singles and the pictures.

(Right: Freddie & Elvis in Paris)

|

|

Ken Sharp: What are your memories of the Elvis Is Back! sessions, his first since coming out of the Army?

Freddy B: He was excited to be back in the studio. Oh yes, he was absolutely delighted to be back recording again.

Ken Sharp: After Elvis left the Army, you adjusted the type of material you presented to him.

Freddy B: That’s true. I presented him with less juvenile songs like “Hound Dog.” I was trying to get him material that was a little bit more sophisticated. But basically the material that I chose for him were songs from writers he liked, whether it was Leiber and Stoller, Otis Blackwell or Pomus and Shuman and so forth

Ken Sharp: Around the period of G.I. Blues, Leiber and Stoller stopped writing songs for Elvis, why?

Freddy B: I got Leiber and Stoller involved in writing songs for Elvis like I got all the other teams involved. I would give them assignments and they

started to write for Elvis. It was a question of ego. I think they wanted to have songs done in a certain way and Colonel wouldn’t agree to it. Leiber and Stoller didn’t get on with Colonel Parker, which was always fatal if you wanted to do business with Elvis.

Ken Sharp: What’s your take on the “movie” songs?

Freddy B: There was a time when Elvis was doing four pictures a year for MGM. It was a real drag. For these movies I had writers like Ben Weisman, Pomus and Shuman, and Tepper and Bennett. They were able to look at scripts and come up with songs that would fit. Leiber and Stoller were reluctant to put too much effort into sitting down with scripts and coming up with songs on short notice. Giant, Baum and Kaye and (Ben) Weisman and (Aaron) Schroeder really wanted to get Elvis to record their songs. They would sit and look at the movie scripts and try hard to fit songs into particular scenes. It became apparent when you read the scripts what kind of a song should go into a particular spot. I’d go through the scripts and determine where songs should go fitting a particular scene

Things had to always be done in a hurry for the films. It was not really inspirational. The songs did not amount to big hits. There were some good ones that came out of the films but it would have been better if Elvis had done less pictures. Then of course he always wanted to have a title song for a picture and it was very difficult to get a good song out of a title like Harum Scarum or anything like that.

When he did the movie songs he would record them in California. I would go out to California and we’d be in the studio and would present the songs to Elvis. Elvis would always choose the material. I would present demos, which were on acetate. He’d always have a choice of at least two or three songs for each scene and then he would choose which one to record.

Ken Sharp: What were the greatest challenges you faced working for Elvis?

Freddy B: It was very difficult to come up with 48 songs in a year’s time. When we got through with one picture there was already another one. Usually I was baffled by a title like Wild In The Country and that became a bit annoying but you had to do it. They were always rather insistent to have hit title songs, which was difficult to do with some of the titles they gave the pictures. But there were some good songs in some of the pictures like “Bossa Nova Baby,” which was in Fun In Acapulco. Others were particularly more difficult, specifically the songs for the MGM pictures used to bug the shit out of me. The movie company was always in a hurry and it had to be done as cheaply and quickly as possible. That was unpleasant. Elvis was frustrated by the quality of the movie material. But he was a professional and was terrific. He’d sing certain songs over and over and over until he got it just right.

Ken Sharp: Elvis had a career downturn in the early Sixties for several years, can you pinpoint why?

Freddy B: The drop off was due to the fact that Elvis didn’t tour. He was involved so much with motion pictures that he didn’t go on the road and lost the connection to the people. It was all that movie stuff. Most of these soundtracks came out and he didn’t go into the studio to just record songs per se. In the Sixties he had a contract with MGM where he was doing four pictures a year for (Joe) Pasternak. It was challenging to find good songs. It was frustrating for me, particularly when you got finished with one movie score, they’d immediately send me 12 scripts for the next score. The reason why I asked for 12 scripts is because I gave it to various writers and wrote off the places where songs would fit. The deadlines were reasonably tight. Elvis had to do four movies a year so every quarter more songs were needed.

Ken Sharp: In hindsight, could anything have been done to improve the quality of the movie songs?

Freddy B: I don’t see how because what it called for was mass production rather than quality. That’s what the problem was. We needed songs on a mass production line rather than looking for quality songs. Back in the Fifties, we used to edit songs and Elvis would have some ideas until it was perfect. Everything related to the movies was done in such a hurry. There was always time pressure.

Ken Sharp: Was Elvis embarrassed by the quality of some of the movie songs?

Freddy B: Yes, absolutely.

Ken Sharp: Were you embarrassed by some of those movie songs?

Freddy B: Yes, of course. I felt very unhappy with all of the crap songs. It was not very good in the Sixties with those kinds of songs but he was doing very well financially

Ken Sharp: How did the situation with Chips Moman not relinquishing publishing on ”Suspicious Minds” and ”Mama Liked The Roses” open up things in terms of Elvis being allowed to more freely seek non-Hill & Range material.

Freddy B: The scope of material he would record from then on was a little widened but not much. First off, Elvis was always looking for a hit song. But his second consideration was whether he was gonna get a slice of it. That’s only natural.

Ken Sharp: Was it commonplace for the writers to give up part of their publishing?

Freddy B: Yes. In a few instances Elvis would cut himself in as a co-writer like on “Don’t Be Cruel” and maybe on “All Shook Up.” But this was primarily done with the publishing. It was understood as far as the film scores were concerned that they’d be all published by Elvis Presley Music. The writers would give up the publishing rights, which they would give up normally anyhow. The songwriters would get a regular SGA contract from the Songwriter’s Guild. They would always get 50 % of the writer’s share and the publisher would get 50 %.

Ken Sharp: You were in the studio and witnessed first-hand the work of producers Steve Sholes and Felton Jarvis. Can you characterize their talents?

Freddy B: Steve Sholes never actually produced a session for Elvis. He would get things together. He was a top executive at RCA but he never ever directed a session. Felton Jarvis would. There were others who did too, people like Chet Atkins. I liked Steve, he was very nice but he was really very much involved in administrative things with the motion picture companies and the soundtracks and so forth. But he never ever produced a Presley record. It was primarily Elvis who produced those sessions, sometimes it was Chet Atkins. Felton was a very capable producer and had very good ears. He would not let any mistakes go by. Elvis liked Felton a lot.

Ken Sharp: For many of Elvis’ sessions he would often warm up for hours by singing gospel music, all while the studio clock is ticking. Were there ever any moments that you felt worried you wouldn’t have enough time to get the songs recorded that were slated to be done?

Freddy B: Yes. He would get sore at me. I’d say, “Listen, you’re wasting all this time here.” Elvis’d say, “You know me well enough, I have to get in the mood to record.” It wasn’t very pleasant.

Ken Sharp: In the 70’s most of what Elvis recorded were melancholy ballads and the occasional rocker like “Burning Love” and “T-R-O-U-B-L-E.” Why did he lean more on recording ballads at the time?

Freddy B: I would always pitch Elvis all kinds of songs but those ballads were the ones that he selected. That’s what he wanted to do. If he selected only ballads it was because he was in a sentimental mood I think he felt more sentimental and ballads fit that. He felt more sentimental at that time than when he was a wild rocker. I think it was difficult for him to have Priscilla walk out. He was not very faithful but he took it hard.

Ken Sharp: Discuss what led to your decision to split from Hill & Range.

Freddy B: I organized Belinda Music in London. It was a wholly owned Hill & Range company and it became quite successful. Then at one time the Aberbach’s needed some money and tried to sell Belinda Music and they couldn’t get more than $600,000 from CBS. I told them I was gonna give them a million and they sold it to me in 1966. In the back of their minds I felt they didn’t think I was going to be able to make it because they thought I was depending on the Hill & Range representation in England. I had to take out a lot of money in a loan and they were guaranteeing the loan. They thought I was going to default on the loan and that they were going to be able to step in and get the company back. When they realized it wasn’t gonna happen they got sore and they fired me in ’69. Then I went into business with Leiber and Stoller with the publishing company, Hudson Bay Music.

Of course, Julian Aberbach tried to get me fired from Presley Music and the Colonel wouldn’t have it. So the Colonel organized new companies and we split the ownership of the companies, Elvis Music and Whitehaven Music. And I had all the new material. That didn’t endear me to the Aberbach’s either. But in the end Jean and I made up. Anyhow, I went into business with Leiber and Stoller. We bought Commonwealth United Music; I had 50% and Mike and Jerry each had 25% and then we bought other companies and went on from there. I brought them back to write for Elvis in the Seventies.

Ken Sharp: Share you memories of some key songwriters and songwriting teams that wrote for Elvis starting with Leiber & Stoller.

Freddy B: Jerry and Mike just kind of meshed together. I thought Jerry Leiber was an extraordinary lyricist. Mike was a very good melody writer. Mike would listen to Jerry and it worked out very well. They’ve been together for so many years and still are. There was a real chemistry there. Leiber and Stoller were personal friends of mine. As I said, I eventually went into business with them with The Hudson Bay Music Company. Leiber & Stoller

Ken Sharp: Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman

Freddy B: I was very close to them as well, particularly Mort Shuman who later came to London; I worked with him in London also. Pomus was very much involved in jazz and black music and Shuman could adapt easily to that. So that combination worked well. Once a song had a feeling of black music I knew Elvis would go for it. Shuman had that kind of feeling in his melodies and Pomus was able to put the proper lyrics to it. Pomus was really a great blues writer and he used to sing. He had just hit it off with Mort Shuman and they became a terrific team. They worked in our office at Hill & Range. Mort’s talent as a writer was more music than lyrics. Later on he wrote with Jacques Brel.

Ken Sharp: Otis Blackwell

Freddy B: Elvis loved Otis Blackwell. Otis had a feeling for black music that Elvis liked. For example, “All Shook Up” was an expression that got to Elvis and it was kind of a black expression. Otis wrote some terrific songs but he wouldn’t write many. But those that he wrote were very special, whether it was “Fever” or “Don’t Be Cruel” or “All Shook Up” or “Return To Sender.” He also had hits for other artists like Jerry Lee Lewis with “Great Balls Of Fire.”

Ken Sharp: Giant-Baum & Kaye

Freddy B: They primarily contributed songs for motion pictures. They had the talent to take a scene from a script and write a song for it.

Ken Sharp: Aaron Schroeder & Wally Gold

Freddy B: Besides the ones that they produced for pictures, they did the adaptation of what became “It’s Now Or Never,” which was an enormous hit. “It’s Now Or Never” was one of Elvis’s biggest songs. Aaron was quite talented as a writer but he was primarily a lyricist. Before working with Wally, he wrote a song for Elvis with a writer named Martin Kalmanoff (“Young Dreams”); Kalmanoff was really the musician and Aaron was the lyricist.

Ken Sharp: Ben Weisman

Freddy B: He wrote 57 songs recorded by Elvis. Ben was quite a terrific musician and his demos kind of appealed to Elvis. Most of his songs were made for pictures. That’s how he benefited by it. He didn’t have many of the knockout hits that someone like Otis Blackwell had. Otis only wrote four or five songs recorded by Elvis but some of those were real big hits.

Ken Sharp: Tepper & Bennett

Freddy B: They were in a similar position as (Ben) Weisman. They were able to follow the scripts closely and wrote a lot of very very good songs. Again, they didn’t produce many huge hits with Elvis but some.

Ken Sharp: I understand that Leslie McFarland who co-wrote “Stuck On You” was quite a character.

Freddy B: He really was a character. (laughs) One day he came into our office and tried to arouse my pity that he had broken his arm. He was trying to get money from me as an advance. The first time he came in he had the sling on the right arm and then when he came back a few days later it was on the left arm and I knew that there was something wrong. (laughs) I don’t think he even remembered that he had it on the right arm initially. (laughs)

Ken Sharp: Select an Elvis song that has the most personal connection for you?

Freddy B: One that I personally have a great feeling for is “It’s Now Or Never.” I knew Elvis was playing “O Sole Mio” on the piano. I gave the idea to a few teams to write an adaptation and it turned out to be a real great success. I also really like “Don’t Be Cruel.” It was his first very big hit. There were so many, it’s difficult to say. But I think “Don’t Be Cruel” and “It’s Now Or Never” were the ones that I was closest to.

Interview by Ken Sharp

-Copyright KEN SHARP/ EIN, October 2009 - Published with full permission.

Do not republish without permission.

Click to comment

DO NOT MISS OUT on Ken Sharp's NEW BOOK "ELVIS: VEGAS '69" - Click here.

EIN Website content © Copyright the Elvis Information Network.

Elvis Presley, Elvis and Graceland are trademarks of Elvis Presley Enterprises.

The Elvis Information Network has been running since 1986 and is an EPE officially recognised Elvis fan club.