Thoughts on Flaming Star

- the dramatic movie that Elvis needed -

- Spotlight by Harley Payette - 2009

|

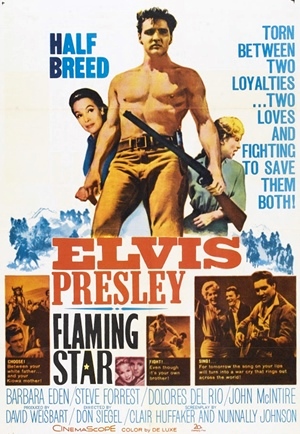

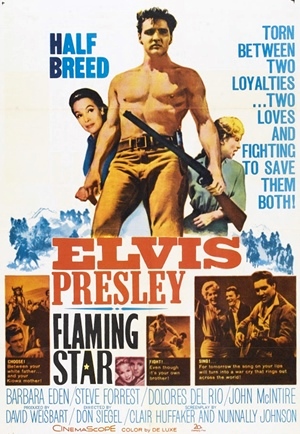

Flaming Star was Elvis' post-army chance to prove himself in a dramatic role and as a serious actor.

Elvis had complained about his previous film 'GI Blues' being so lightweight. He even went as far as telling Priscilla that he was "goddamn miserable" about it.

With terrible timing 'Flaming Star' would be released just 4 weeks after the family-friendly 'GI Blues' and unfortunately it would falter at the box-office.

The 1961 'Blue Hawaii' would confirm the financial success of lightweight musical fluff and Elvis' dramatic interests would then be halted by Colonel Parker.

50 years on EIN contributor Harley Payette takes a well deserved spotlight at this often over-looked film.

|

|

In 2022 Baz Luhmann's massively popular 'ELVIS' biopic changed everything - see below for a 2022 updated discussion on Flaming Star. |

"...lots of action; along with Jailhouse Rock, Presley's best film."

- Leonard Maltin. American critic and film historian.

Thoughts on Flaming Star

Whenever Elvis’ film career is discussed Flaming Star (1960) always plays a primary role in the discussion. This was the serious film that Elvis fought for after his return from the army. Unfortunately, it was greeted with confusion by the movie company, critics and the general public all of whom basically had become accustomed to seeing Elvis in musicals. After this and one other serious dramatic effort, Elvis made Blue Hawaii, a light musical and one of the great box office hits of its era. The success of Blue Hawaii and the relative failure of the dramatic films set the course for most of the rest of Elvis’ generally commercially successful but artistically unsatisfying film career. That meant that Flaming Star became a symbol of what could have been and ceased in many ways to exist as an entity of its own. This is kind of a shame because Flaming Star is a film of considerable merit and an important symbolic achievement for Elvis.

Voted in the Top 100 Essential Westerns

That Flaming Star is a good movie has never been in dispute amongst the few that have seen it. Most of the critical guides rate the film a solid three stars and praise the script and Elvis’ performance. When the British Film Institute compiled a history of the western in the late 1980s, they included it as one of their 100 or so essential westerns.

Don Siegel, the film’s director was pleased with both the film and Elvis’ performance. Oddly, the main dissenters in this point of view have been the rock press. Dave Marsh thought the film was good, but “overrated.” Roy Carr and Mick Farren thought Siegel made his points with “flashing neon lights” and called the story “rife with cheap allegory.” Peter Guralnick panned Elvis’ performance and called the film’s plea for racial tolerance “insipid.”

|

|

I think the rock critics are off base in their assessments; perhaps afraid of being accused of favoritism, they’ve overlooked a film of real substance. Flaming Star is not one of the great films in movie history. But it is a superior work that tells us about the human condition, a real contribution by the screen writers, Siegel and the cast especially Elvis.

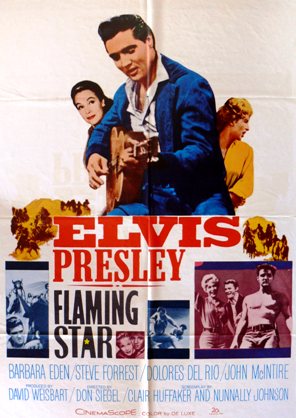

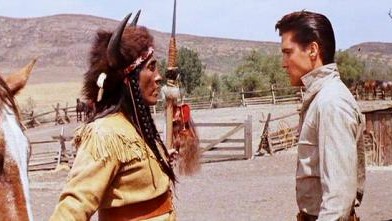

(Steve Forrest, John McIntire, Barbara Eden, Dolores Del Rio and Elvis)

The movie’s plot revolves around Pacer Burton (Elvis), the half-white, half-American Indian son of Sam and Neddy Burton (John McIntire and Dolores Del Rio), a white rancher and his Kiowa wife. They live on Sam and Neddy’s Texas ranch with Clint (Steve Forrest), Sam’s white son from a previous marriage. The family has found an uneasy place in Sam’s white community, while still maintaining some ties with Neddy’s Indian kin. They’re basically happy until a war breaks out between the whites and the Kiowas that forces the Burtons to

choose sides with tragic results.

The story is based on a novel by Clair Huffaker, who wrote the screenplay along with Nunnally Johnson (a superior screenwriter who also wrote the screenplay for the 1940’s The Grapes of Wrath). Watching the film based on their screenplay today makes Guralnick’s comments seem insensitive.

The work that Johnson and Huffaker give us is hardly “insipid.” Granted, you do see the “flashing neon lights” at the film’s climax when Elvis is delivering his speech. “Maybe someday, somewhere, someone will understand folks like us.” However, such moments, are infrequent and do not capture the heart of the script.

Indians, Westerns and the Anti-Racist stance

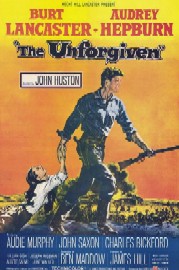

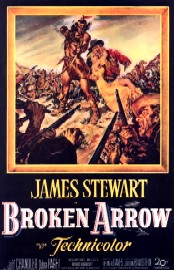

Huffaker and Johnson’s script is actually one of the best I’ve ever seen at capturing the pervasive, natural, casual quality of racism. It does this far better than stuff like 1950’s Broken Arrow, and even John Huston’s The Unforgiven (1960). In fact, I think Flaming Star is one of the most effective films of any stripe in this regard.

The racists in Flaming Star are not all villains. They include not only the Burtons’ friends and Clint’s fiancé, but also Clint and Sam themselves. At one point, when Pacer is overly secretive, Sam complains that maybe Pacer is more than half-Indian. When Pacer is doing something of which his father doesn’t approve, he’s Indian. It’s a little line, but it demonstrates that even with his father there’s a little part of Pacer that does not fit in.

Clint’s dialogue is sprinkled with these little bits of racism. At one point, he tells his father (out of Pacer’s ear shot) that “An Indian will rob you blind if you let him.” There’s another scene where he almost seems as sorry for the man who shot his step-mother as he is for her until Pacer brings him back to Earth. None of these comments are meant to insult Pacer or any Indian in particular. They’re just un-thinking bits of conversation.

Unlike in Broken Arrow, there are few avowed racists who despise Indians just because they’re Indians. But there are even fewer whites who genuinely like or trust Indians. Even those who like Indians like Clint or his fiancée Ros (Barbara Eden) prefer the company of whites and distrust Indians.

The scene where Elvis confronts the couple with this information packs such sting because Pacer genuinely loves both. We learn that Pacer and Clint are extraordinarily close brothers, who have never had a single fight in their young adult lives. Yet, in this confrontational scene, Pacer confesses a secret youthful passion for Ros that he has only previously expressed to his mother. Even the brothers’ extraordinary closeness is limited by Pacer’s racial heritage.

| Pacer and Clint are the best of friends, but Pacer doubts that Clint can sympathize with the reality of the racism he endures and judging by Clint’s comments, he’s right. When Pacer is walking out the door to join Buffalo Horn, Clint comments “Good God Pacer! You’re a civilized human being.” By this of course, Clint means Pacer is white. This is the self-deception that allows Clint to love someone who would “rob you blind if you let him.” |

|

Pacer never expressed his love for Ros for even tougher reasons; she could never love an Indian. In the film, Ros is a relatively enlightened character who genuinely likes Pacer and his mother. Yet, when Pacer and Clint come into buy supplies after a local family has been slaughtered by warring Indians, Ros gets into Pacer’s face to deliver the news in a confrontational accusatory manner. Clint, of course, understands this, even as he takes offense for Pacer, because Pacer is an Indian and Indians did the damage. So, it is understandable that she would lash out against the nearest Indian. The lie behind this thinking, which the film lets us know Pacer understands, is that if the family had been murdered by a group of marauding white bandits, Ros would have never condemned or confronted Clint in a similar manner. Ros sees Pacer as an Indian first and a person second.

This revelation is a key to why Pacer never confessed his infatuation. No matter, his merits, Pacer’s case for Ros’ affection would never be good enough. This was a part of the inspiration in casting Elvis in this role. In 1960, there was a not better looking man on the planet than Elvis Presley. His beauty immeasurably aids the story because it shows just how far Pacer was from achieving full humanity in the white community. Had his features been on a white man, white women would have been circling around him. As a half-Indian, Pacer’s beauty means nothing; he must keep his deepest love to himself.

| Pacer, to his credit, never falls for the idea that he is an honorary white. When his brother suggests that he’s a civilized human being, Elvis contradicts him “No, the people at the crossing are civilized, not me.” When an Indian friend asks if white men treat him well, Pacer answers definitively “My father and brother do.” There is no qualification. |

|

While the dialogue of Pacer’s friends and family gives us an appreciation of racism’s pervasiveness, racism’s impact on human behavior is amply demonstrated in remarks made by two trappers who impose upon Pacer and his mother for a bite to eat. The men approach the house with sheepish trepidation. When Neddy invites them in to eat, they are grateful. Once they are in the house and find out that Pacer and Neddy are Indians, their attitude changes.

They immediately assume the Burtons are servants. When they find out that is not the case, one of them blurts out, “How do you like that? Injuns…living in a house like this.” Significantly, this comment is made not under the trapper’s breath, but out loud directly in front of Pacer and Neddy. It is even more flabbergasting because these comments are made by a guest in the Burton’s home.

These few seconds of film provide tremendous insight into the racist character. The fact that the trapper makes the comment as if the Burtons are not even in the room is indicative of the instant lack of humanity that the racist sees in other races. He doesn’t think if his hosts will be offended by his comments. He doesn’t care. They’re Indians, they deserve to be insulted. They should know that.

The viewer sees it as well in the shift in the power structure perceived by the trappers. Not only do they insult the Burtons, but the same men, who minutes before were begging at the door, start to issue orders when they come in the house and find Indians. From all they’ve been taught in their lifetimes, the Indians are their inferiors who should be grateful to serve a white man. No humility is necessary.

Watching this shift in attitude, it is easy to understand the actions of racists like the Ku Klux Klan or the Nazis. When you don’t see the other race as equal human beings, when you instantly mark them as inferior upon discovering their race, the floodgates are open. Most of us don’t even blink an eye when we swat a fly. For people like the trappers in this movie, the Indians are like more dangerous flies. That people of other races might have feelings of their own is not conceivable to men like this.

The revealing dialogue lines that make these points are mostly all tossed off asides. In no way are they the pushed forth with the neon lights that Carr and Farren see.

The film’s dialogue and overall story arc do not flinch from the ultimate impact of racism on the lives of individuals and society as a whole. Save for Clint, the entire Burton family dies. It is significant that its only survivor is the man one character calls “the only real white man in the family.” The Burtons are from the only victims of the full blown race war in progress. At least two additional white families (one off camera) are wiped out. Dozens of Indians die including Pacer’s childhood friend Two Moons.

Plus, there is an overall air of paranoia and dread that pervades the life of all the characters. In one scene, we see wagons coming into the town to find protection in the war. We are told families are coming in every day. Moments before Clint comments “It’s just pure hate now, with everybody ready to kill anyone that’s not just like them.” Imagine living in such an environment. |

|

Far from being the insipid plea for racial tolerance that Guralnick sees, the film follows racism to its logical ends. Devaluing the lives of one race, devalues, and potentially destroys, all life.

For Pacer and Clint, family is their only salvation. Pacer eventually turns and fights against his fellow Indians, not because the Indians are on the wrong side of the war, but because they have attacked his brother. That his brother instigated the conflict is not a concern; this is family. His final action is to make sure his brother is alive. He gives his life to Clint in the hope that he will live to see a world where race doesn’t matter. Perhaps he realizes that as a “real white man” Clint will have at least some chance of happiness in a world full of racial hatreds and dominated by the white race.

Clint’s actions at the end give the audience its only sliver of hope. Freed of Pacer, his step mother, and his racial sell-out father, Clint finds himself welcomed into the white community that only recently despised him. Clint, however, is having none of it. He wants out right away, presumably to find Pacer. Even after Pacer comes and leaves, it is clear that Clint will not be staying with the whites who have treated his family so abhorrently. The film ends with Barbara Eden preparing Clint’s horse for his departure.

Whether Clint’s decision represents a new awareness or is simply a statement of familial solidarity is left ambiguous. The second interpretation seems more likely. From all we’ve seen, Clint’s disillusion is largely based exclusively on Pacer’s plight.

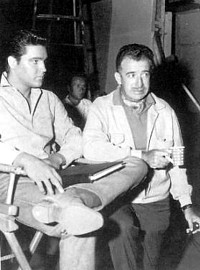

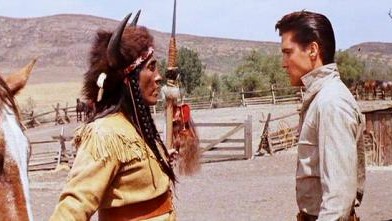

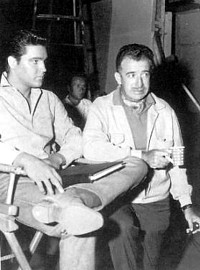

Director Don Seigel supporting Elvis in his dramatic role

As fine as Huffaker’s and Johnson’s script is, Flaming Star is as successful as it is because director Don Siegel and his cast so vividly drive the action home. Siegel has several stand-out scenes including Elvis’ fist fight with the trappers and the initial Indian attack. For many of the film’s highlights he opts to play his scenes without music, using silence as its own statement. This roots many of the film’s most dramatic moments in an almost documentary realism. As Elvis and Steve Forrest fight, you almost cringe when all the sounds you hear are the two men scuffling and Elvis’s gasps for air as his brother clenches his neck.

Siegel’s decision to fight the suits and limit Elvis’ songs to the title credits and a party in the opening minutes was crucial. To have Pacer sing amidst all the death and hate he encounters would have strained the film’s credibility. When Pacer is considering whether or not to join the Indians in their battle against the whites- maybe killing people he once thought of as friends- he is not in the mood to sing.

|

|

The cast is uniformly fine. It’s hard to pick a stand out. Del Rio and McIntire help the film by plying their stocks in trade, gentle mysticism for the former and matter of fact intelligence from the latter. Steve Forrest gives his role a reserved dignity and his chemistry with Elvis is amongst the strongest of any male co-star in an Elvis movie. Forrest helps underline the closeness of the brothers with several little moments. The best of these is in the film’s opening party when he takes a jug of liquor and places it under Elvis’ nose while Elvis is trying to sing his song. It’s the type of tease real siblings often engage in.

Barbara Eden, though, was an especially inspired choice. Reportedly, horror movie queen Barbara Steele was the first choice for the role. However, her personal hardness and dark hair were all wrong for the role. Eden’s golden locks make her perfectly cast as an unobtainable white princess. Plus, she brings a down to earth gentleness and folksy quality to the role. It’s easy to see why Pacer would like her because she comes across as funny and decent.

Elvis' Challenge.

Center in it all is Elvis. No dramatic part ever suited Elvis better. As the ultimate cultural mix of black and white, Elvis would seem to have an understanding of the nether world that Pacer occupied. Granted, Elvis was not a half-breed, but spiritually he had to understand the pull between two cultures living together at loggerheads. (Elvis did have some Indian blood as his great, great, great grandmother Morning White Dove was a full blooded Cherokee.)

The entire film depends on him and it would not be the success that it is without the credibility he brings to Pacer. Beyond his obvious suitability for such a character, Elvis’ line readings and movements are more than competent, and many times much better. When he decides to pull a gun on Clint after losing their fight, he clenches his teeth, a gesture that suggests the reactionary nature of Pacer’s decision. Earlier in the scene, he mellows his voice considerably when discussing his love for Ros and the pain of keeping it to himself. It’s a touch of vulnerability that helps us understand the sense of rejection at the heart of Pacer’s anger.

|

|

This is not the only place where he shines though. He is also quite effective when dealing with the trappers who tried to rape his mom and in a scene where has to hold a child hostage. And, he has great chemistry with Del Rio. The moment where he smiles and pulls her to his chest after besting the trappers is maybe the most emotional moment in the movie.

There are a few demerits. Most of these come in Elvis’ scenes with the Indians where he speaks in halting, affected manner, altering his rhythms to almost speak in an accent without an accent. It’s a period flaw, but it’s a flaw nonetheless. Still, it’s not enough to derail a strong interpretation of an extremely difficult part.

Like Elvis’ performance the film itself falls short of perfection despite of its many virtues. The final 25 minutes or is very confused in its action and seems to rush the story to its conclusion. Cyril J. Mockridge’s score is overemphatic and pushes Del Rio’s death scene, an already melodramatic scene, over the top.

While the film, unlike Broken Arrow, is even handed in its depiction of racism (Neddy’s own sister rejects her for marrying a white man), its articulation of the Indian viewpoint seems stock. (I.E. We do not take their land etc.) And, some of the Indians’ dialogue is a little florid.

(In another consideration, all video versions of the film seem to have a tinny soundtrack.)

Poor Marketing

Still, Flaming Star has so much going for it and deserved a better reception from audiences and critics. However, the studio- 20th Century Fox- fudged its marketing of the movie. The studio 20th Century Fox marketed it as a musical and the studio used that as a key in its promotion. As a result, fans hoping to hear Elvis sing were disappointed and critics and film partisans who may have championed this heavy hitting movie, were never steered in its direction.

This is a shame because the movie not only has something to tell us about our world, it also provides cultural historians an important insight into Elvis Presley’s career, character and decision making.

If there is one consistent criticism of Presley’s career management, it is that he did not take a strong enough hand in decision making. Generally, he is seen as too passive and not in control. However, Flaming Star is an example of a moment where he did take control.

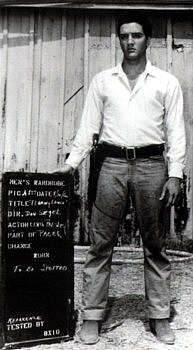

(Right: Elvis with director Don Seigel) |

|

When Elvis got home from the army, his first movie was GI Blues, a light Bing Crosbyesque musical with a mostly uninspired soundtrack. According to Presley’s wife Priscilla, with whom Elvis discussed the project by phone, and other Presley insiders, the singer was not at all pleased with GI Blues and he pledged to get better a project with his next film. Apparently, he made good on this pledge as Flaming Star and Elvis’ next film Wild in the Country (which had a screenplay by the legendary Clifford Odets) were dramatic heavy hitters.

|

This is a significant fact. Contrary to legend, Presley did indeed fight for better film projects and got them in the form of these two films. However, neither of these films were supported by Parker or the studio heads and consequently neither project lived up to the usual Presley commercial expectations. Also, a neither was a completely flawless dramatic project like The Godfather, and did not receive the kind of critical or industry acclaim that could have led to more projects of this kind. To Elvis, it must have seemed a failure and a validation of Parker’s and the studio heads’ strategy. This impression was furthered by the spectacular success of Blue Hawaii.

|

Although neither of Presley’s dramatic efforts was a success in its time, and Elvis never tested these waters again in such a full hearted manner, it must not be forgotten that he made an effort to make significant cinematic art. It wasn’t all bubble headed fun.

Perhaps even more important than the little insight into a moment where Elvis took charge of his movies is what Flaming Star tells us about Elvis’ views on race. As Elvis came to prominence during a period of racial segregation and performed in a style heavily influenced by black performers, Elvis has often been accused of stealing black culture for personal gain. To give the charge added legitimacy, Elvis has often been accused of being a white supremacist. (When you’re arguing that someone ripped off a culture by performing within that culture, it muddies the waters when you consider that person legitimately loved the culture.)

Elvis’ presence in a racial treatise as effective as Flaming Star is a strong rebuke to the idea of Elvis the racist. No legitimate racist would ever star in a movie like Flaming Star. |

|

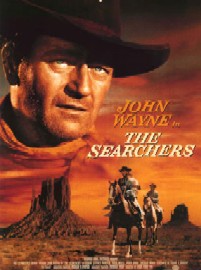

Flaming Star vs other period Westerns

Flaming Star was released at the end of 1960, a time when the battle for/against the Civil Rights of blacks was at its height in the US. One of the advantages of the western form was that it provided a necessary distance in time from contemporary social problems to allow those problems to be played out by proxy on the screen. While the race war that resulted in the ultimate genocide of the American Indian was all too real, the on screen clash between whites and Indians held a mirror up to what was happening in the streets between whites and blacks. While many audience members chose just to see a western, most thoughtful audience members easily saw the parallels in films like The Searchers, The Unforgiven, Broken Arrow and others.

In this tradition, Flaming Star is exceptionally tough. Unlike The Searchers (1956) or the earlier Fort Apache (1948), the racism is not portrayed as an aberration of a few individuals or a callous government, but entrenched in an entire culture. This is a trait that separates it from movies that tried to address the contemporary black/white cultural divide like 1950’s No Way Out and 1959’s Odds Against Tomorrow. Certainly, the distance of the Western helped in this regard. Such a condemnation of white culture would have certainly have kept any contemporary film off screens throughout the South.

In no way is the white culture deemed to be superior. The minority culture is meant to be an equal. When Elvis steps away from his family to take up with the Indians, the film disapproves of his action because he is choosing a life of violence. However, when Elvis turns against the Indians, it is only because of his family. When he dies, he makes the choice that he wants to die in the hills as an Indian. The film is much stronger in this aspect than the same year’s The Unforgiven where it is evident that Kiowa Audrey Hepburn plans to stay with her adopted white family.

This aspect of the screenplay is exceptionally important when one considers Elvis’ potential attitudes on race. Would a white supremacist appear in a movie that so strongly condemns his culture’s attitude on the issue? Would a white supremacist make a movie that promotes cultural equality with what he/she believes is the inferior culture?

More importantly, Flaming Star directly tackles miscegenation, the greatest fear of 1950s/1960s segregationists. The film does not place mixed marriage on any special plane, but it does plead for tolerance and understanding for those who make that choice. Pacer is the child of the mixed marriage and therefore Elvis plays a person of mixed blood. In 1960 there would have been no greater insult to a white supremacist than to have mixed blood. The very idea that mixed marriages should be tolerated was anathema to these people. That Elvis would play a character of such origins and make a movie carrying such a message says a lot about his point of view on this issue. Even movie stars do not appear in pieces that repudiate everything they believe, and they certainly don’t seek such projects out. (The film’s depiction of miscegenation made racist officials in South Africa so queasy that they banned the film.)

A contemporary viewer may have some trouble with the fact that Elvis dons (some very effective) light red makeup for his role. However, this is not minstrel makeup. Elvis wears the makeup in this movie not to belittle American Indians, as many minstrels belittled American blacks with their blackface. Instead, he wears the makeup in a project designed to increase sympathy and understanding of non-whites, something a white supremacist would never do.

It was a period commonplace to have whites play Indians in the 1950s and 1960s. However, this case is more appropriate than many of those casting choices because Pacer is neither white nor Indian. Other than casting a person of genuine mixed descent, this was the best Hollywood could do in this circumstance. And placing an established star like Elvis Presley in the role increases identification with the character.

Whatever its genesis, the makeup makes a strong point. When all it takes is some red tint on his skin to turn a national heart-throw like Presley into a social pariah, it makes a statement.

Flaming Star's Place in History

The initial commercial reception accorded to this insightful project has left Flaming Star something of curiosity known only to Presley and western diehards and some rock historians. This is a turn of events that need to be reversed. While not a truly great film, it does offer the thoughtful movie fan many rewards and deserves to be rediscovered.

Spotlight by Harley Payette.

-Copyright EIN May 2009

Click here to comment on this article

|

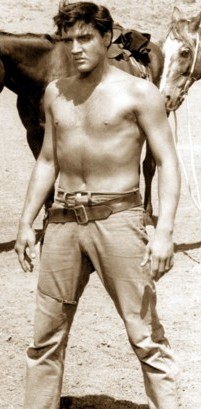

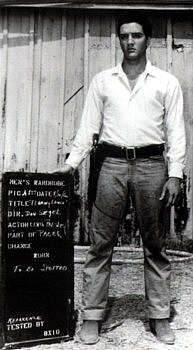

Two images of Elvis on the set of Flaming Star |

|

September 2022 - Flaming Star - The greatest film you never saw: David Crow, Movies Editor for the popular review site, denofgreek, published an excellent review of Flaming Star. Here is an excerpt...

... There’s a reason Luhrmann’s 'ELVIS' epic spent only a scant 102 seconds on Presley’s years in Hollywood: the vast majority of movies he made were awful. So much so, they derailed his career as a rock ’n roll rebel, leaving him in a precarious place where by ‘68 he had to decide if he wanted a musical comeback or to sing Christmas jingles on TV for the rest of his life.

Even so, Elvis’ movie career could have gone a different way. And if you only want to spend your time on watching one movie that shows that potential, your best bet is 1960’s Flaming Star.

Directed by Don Siegel (Invasion of the Body Snatchers / Dirty Harry) and released in 1960, Flaming Star really was one of those first few films Presley made after getting out of the Army, attempting to become another Dean or Marlon Brando. Indeed, as originally conceived by 20th Century Fox, Flaming Star was intended to be a vehicle for Brando and Frank Sinatra. That of course never happened, perhaps because no one told them that Sinatra despised Brando after working with him on Guys and Dolls (1955). The years, and later The Godfather, did not make the heart grow fonder for Ol’ Blue Eyes.

In any event, when it became clear that Flaming Star would not be a star vehicle for the most interesting young actor of the 1950s, plus a popular singer(!), the Western was reimagined as an experiment for a young actor who also was a popular singer: Elvis Presley.

|

|

In the film, Presley stars as Pacer Burton, a half-white and half-American Indian rancher’s son. Pacer grew up in the wilds of 1870s Texas where his white father (John McIntire) and Kiowa mother Neddy (Dolores del Rio) raised him and his white half-brother Clint (Steve Forrest) as equals. Theirs is a genuinely loving inclusive family. But after a Kiowa raiding party brutally attacks a nearby homestead, tensions swell between white Texans and Native Americans again, and the Burton family finds itself in the crosshairs of both sides, with

|

|

Pacer particularly being the subject of vitriol and suspicion among former friends and neighbors who would kill his father’s cattle before letting the lad sing another ditty to their lily-white daughters.

To modern eyes, there are all manner of trigger warnings required for a movie like Flaming

Star: the film is rife in the sentiments and prejudices of 1950s America, not least of which include casting all-white Elvis as the “half-breed” Pacer, and the Mexican del Rio as his fully Indigenous mother. There’s also no particular good explanation for how Presley’s Pacer perfected his greaser pompadour in the 1800s.

However, the movie’s strength is how straightforward and grimly self-aware it is about the racism of its subject matter. Here is a film produced in what was still the then highly segregated 1950s in which the hero (and not the John Wayne sidekick) is of a biracial background, and most of the conflict derives from how the white characters react to this fact. At the beginning of Flaming Star, Presley has his one tacked-on singing sequence where Pacer croons a birthday barnburner for his neighbors before the killing starts. (Presley apparently insisted the two other songs intended for the film be cut so he could be taken more seriously as an actor.)...

Read the full review here -

(Film Review, Source: David Crow, Movies Editor, Den of Greek/ElvisInfoNet) |

|

|

|