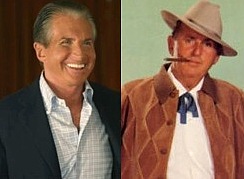

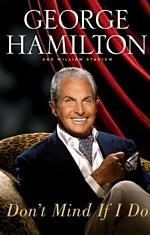

Hamilton, who now spends most of the year in Palm Beach, Fla., is discussing his self-deprecating and witty autobiography, "Don't Mind If I Do," which he wrote with William Stadium. He's the first to admit that his life has been "absolutely outrageous." Hamilton had a wild upbringing with a much-married mother who travelled the country with her three sons looking for love and a father for her children.

Along the way, he lost his virginity by the time he was 12, became a movie star before he was 20 and bought booze for Robert Mitchum while making his first MGM picture.

"Films were pale to what my life was," Hamilton said.

Though he's had tragedies in his life, such as the alcoholism-related death of his older brother Bill, the book isn't a tell-all weepie. "There is an old expression: Life to the feeling man is a tragedy and to the thinking man a comedy," he noted. "I never copped a plea on good behaviour. I never took it that way. I remember sitting with [David] Niven and listening to him tell stories. Michael Caine, I love listening to Michael's stories. And that is the way I saw my life. The joke was always there."

"Don't Mind If I Do" is filled with juicy anecdotes about the women in his life -- including actress Susan Kohner, to whom he was engaged; Elizabeth Taylor; Lynda Bird Johnson; Danielle Steel; and his ex-wife, Alana. It also recounts his years under contract at MGM in the early 1960s, when he made films including "Home From the Hill," "Where the Boys Are" and "Your Cheatin' Heart"; his career ups and downs; his comebacks in such comedies as "Love at First Bite" and "Zorro, the Gay Blade"; and his stint on "Dancing With the Stars."

Along the way he forged friendships with the likes of Grant, Mitchum, George Peppard, Imelda Marcos and even Elvis Presley's notorious manager, Colonel Tom Parker. The publicist assigned to Hamilton while he was making 1960's "Home From the Hill" for director Vincente Minnelli suggested he give Parker a call about becoming his manager. The Colonel was only handling Elvis but suggested that Hamilton look him up on the MGM lot.

They finally met about six months later and became fast friends. Though the Colonel had the reputation of being a charlatan and even misguiding Presley's career, Hamilton says that was far from reality.

"I saw The Colonel operate and saw what he did for Elvis and how smart he was," said Hamilton. "The Colonel would say to Elvis, 'You can't be in film and on stage at the same time. You don't want to compete with yourself.' Elvis didn't want to work that hard. He liked to be with the Memphis guys. He liked to play paddle tennis and play touch football. And you had a choice -- you could either be Elvis' friend or the Colonel's friend."

Being part of the Hollywood crowd in his early 20s, he recalled, was surreal. "All of a sudden I'm in a room, and [movie stars] are talking to me like a human being," he says. "It was like I had been thrown into a movie screen from a seat in a movie house and I couldn't quite believe it. I'm talking to Robert Mitchum and he's bigger than the guy onscreen."

On choosing Colonel Parker as a friend...

I was still in pain over my future partner Alana Collins. I headed for Palm Springs, where I had been renting a house. It was 1972. Alana was there collecting her things in preparation for her move to England and ladyship. Lichfield had gone to Fiji and would be picking up Alana on his way back.

We had a farewell dinner with my friend Colonel Tom Parker, Elvis's manager, who lived nearby. Seeing how sad I was, Parker took me aside and gave me some fatherly advice. I had to handle Alana like a negotiation, he said.

'She may be bluffing,' Parker continued, 'but you care too much to risk losing her.

'You better stay in the game,' he concluded. 'She's a lot smarter than you, boy. You better marry her.' |

|

To seal the deal, he offered me Elvis's plane to fly to Las Vegas and tie the knot. There was one caveat. If I was going to do it, I had to do it now. Right now. 'There's a ten o'clock movie I want to watch on TV tonight,' Parker said. 'We've got to be back for that.'

I took his advice, but thought it would be impossible to compete with 1,000 years of British pomp and circumstance. But, oddly enough, Alana, like Britt, was put off by the tourists at Shugborough.

I got down on my knees, Alana said 'Yes' and off we went in Elvisair, with Parker and Alana's cockapoo (a cross between a cocker spaniel and a poodle) dog, Georgie. Colonel Parker reserved the top suite of the International Hotel for the ceremony and he rounded up a drunken preacher to whom I paid $30 for the vows.

Parker was my best man, Georgie was maid of honour, and a dazed waiter was enlisted as a witness. Parker and I played roulette and won $15,000. Then we got back on the flying Elvis and spent our wedding night in Palm Springs while Parker watched his movie.

After I had married Alana, the gods of Hollywood smiled on me and my most recent film, Evel Knievel, opened to big numbers. I forgot all thoughts of a medical career.

Our son Ashley was born in 1974, the most beautiful child I could imagine, but he couldn't save our marriage. Alana and I divorced in 1975.

I can blame it only on our youth. I wanted to settle down, but had chosen the least settled-down woman on the planet. I think that Alana reminded me of my mother: pretty, funny and Southern. I wanted someone soft and feminine-but underneath that goddess was a cowboy as tough as John Wayne.

Alana later married Rod Stewart, with whom I shared a seemingly identical taste in women. We had both been involved with Britt Ekland and we both dated Liz Treadwell, my off-and-on girlfriend for more than a decade.

In my early 50s, I met Kimberly Blackford, a beauty in her 20s. We dated intermittently for several years and she is the mother of my second son, George Thomas Hamilton (GT for short), who was born in 2000. I wish that I had been the marrying kind, but I wasn't. However, GT and Ashley are the two bright stars in my life.

Robert Mitchum's thirsty work

I worked with Robert Mitchum on the 1960 film Home From The Hill and I never saw any star care less about being one. Bob could talk your ear off, but the one thing he didn't want to talk about was his lines or the film. He liked to get drunk and then sing songs - sea shanties, cockney ditties, Australian football songs, anything.

What he would usually say to me was: 'Gettin'any?' He was. Bob would send me to buy him liquor. On my first run back to his hotel room, I found him 'entertaining'a lady. He motioned me to open a bottle and hand it over. I was honoured to be of service.

When he wasn't having sex, he'd sit in a rocking chair wearing just boxer shorts and alligator cowboy boots while casting for imaginary trout with a fishing rod.

He drank a lot and smoked a lot of dope. He also took a lot of pills, which he kept in his own leather doctor's bag. One night I asked him for something to help me sleep. He handed me a pill he called a 'nighty night' - and I slept straight through my call the next morning and on into a second day.

Bob once said to me: 'They think I don't know my lines. It's not true. I'm just too drunk to say 'em.'

The studio once sent a manager to keep Bob in line, but the minute he walked into the hotel room, Bob punched him, knocking him through the door.

For years, Bob sent me Mother's Day cards. I was never sure why, but he gave me confidence that you could always be a star in Hollywood on your own terms.

Saving Elvis from a bad hair day

On August 16, 1977, I received a phone call from Colonel Tom Parker advising me of Elvis Presley's funeral arrangements. When we arrived at Graceland, Elvis was laid out in the parlour in proper Southern fashion: white suit and a blue tie, if I remember correctly.

Elvis looked younger than I remembered. I approached the casket for a closer look. That's when I noticed that his hair had been dyed recently and a little line of black dye had rolled down his ear.

Leave it to me to notice something like that. What was I going to do with this information? Was I the hair dye police? Let somebody else tell them.

But then Charlie Hodge, lead guitarist and the one who always handed the King a replacement scarf when he'd tossed his to the crowd, asked me if I didn't think Elvis looked great. He proudly told me he had dyed Elvis's hair a couple of hours before. 'I can see that,' I told him and pointed out the problem.

Later I was told they stopped the funeral for a few minutes while they dabbed away the dye and inspected things.

EIN has its own opinions on 'Gorgeous George'.

Click here to comment on this article

Spotlight by Piers Beagley.

-Copyright EIN April 2009.