|

|

by EIN contributor Pam Harris

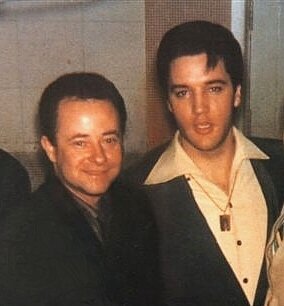

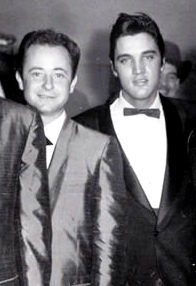

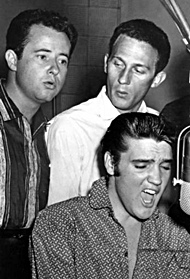

(Above photo: Gordon Stoker & Elvis, May 28th 1966 at the ‘How Great Thou Art’ session)

The following is an excerpt of an article that first appeared in The Weakley County Press (Martin, Tennessee, USA) on May 11, 2004.

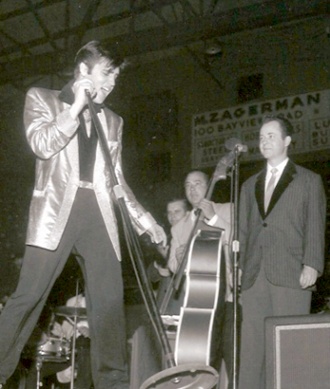

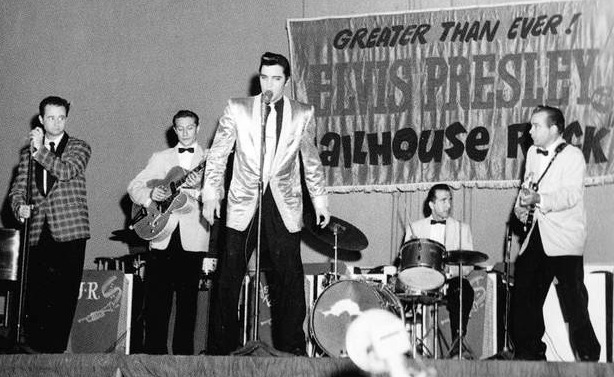

Gordon Stoker could be a name-dropper, if he wanted to be. After all, he has recorded with the likes of Patsy Cline, Jim Reeves, Loretta Lynn and Elvis, just to name a few. His list of co-artists includes more than 2,000 pop and country stars of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, and he has known the joy and sorrow of friendships that ended all too soon such as those with Reeves, Cline and Ricky Nelson, who all died tragically in plane crashes. He could be a snob, if he wanted to be. His awards are too numerous to mention, but the 2003 Grammy for the Best Southern Country Gospel Album definitely stands out as do inductions into several halls of fame, including the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2001. He has traveled the nation and the globe, appeared in movies and on television, and been a regular on WSM’s "The Grand Ole Opry" in Nashville. To someone outside of entertainment circles, his accomplishments are impressive if not overwhelming. But Gleason (Tenn.) native Gordon Stoker is neither a name-dropper nor a snob. He is instead a sincerely nice gentleman who loves his hometown and home county, loves his family and loves what he does—singing and performing with The Jordanaires quartet. He is a humble man and has been content to lend his talents as a background vocalist and musician to singers of all genres. Stoker reflected on his successful career and remembered that a record producer "told us not to worry about making the Hit Parade. He said, ‘The background field will be good to you.’" The producer was right. While other entertainers have come and gone, The Jordanaires are still recording and performing for audiences. "Back-up work is steady," Stoker said. "You’re not here today and gone tomorrow." Steady, indeed. He’s been at it for 54 years, and his 2004 schedule is full. The group just cut a Christmas CD and is preparing to record a bluegrass collection. Stoker recently returned from a performance in Canada and he and the group leave for Ireland at the end of May this year. They’ll be in Tupelo, Mississippi, on June 4 to do an Elvis tribute and in Tunica in August.

Stoker’s musical career began early. Everyone in his family—his parents, two brothers, a sister and Stoker—sang and played musical instruments. His mother and brother Wayne played the guitar. Gordon’s specialties were the piano, organ and accordion. They sang and played at singing conventions—a term used in the south for gospel singing get-togethers—that were common on the weekends in the 1930s. They sang locally but occasionally traveled to Jackson and Memphis. "As far as we could go in those days, we went," Stoker said. Stoker recalled winning his first award at a convention in Weakley County when he was 7- or 8-years-old. He still has it proudly displayed among his other, more prestigious honors. "I sang ‘Have you ever been lonely, have you ever been boo,’" he said, chuckling over his youthful mispronunciation of the word "blue." He also won medals at various competitions for being the best pianist. His real break came, however, when at age 12 or 13 he impressed John Daniel of The Daniel Quartet, regulars on the Grand Ole Opry. Stoker was at the annual Snead Grove picnic, which drew thousands of spectators to McKenzie to see the showcased talents of local and Opry stars, when Daniel heard him perform with the Clement Trio of McKenzie. Stoker was the regular piano player for the group, which had garnered quite a bit of local recognition. When Daniel heard the young pianist, he was impressed. He asked Stoker his age and told him that he’d give him a call after Stoker graduated from high school. He would, he said, make the young man a star. In 1943, the United States was embroiled in a brutal world war and Stoker was drafted into the Air Force. The same nimble fingers that danced gracefully on a piano keyboard also flew across typewriter keys and enabled him to serve his country as a teletype operator in Australia. There he monitored air traffic and was discharged from the service three years later. Upon returning to the states, he attended college for a while in Oklahoma and then Peabody College in Nashville, planning on becoming a teacher. There he rejoined The Daniel Quartet. Little did he know that his future was being determined by a group of four men—brothers Bill and Monty Matthews, Bob Hubbard and Culley Holt—in Springfield, Missouri, who began in 1948 as a barbershop, gospel and country quartet. They called themselves The Jordanaires. By 1949, they had secured a regular Saturday night spot on the Grand Ole Opry and had also gone through some personnel changes. Bob Money, their pianist at the time, was drafted and Stoker auditioned to be his replacement. He got the job. The Jordanaires continued to be regulars on the Opry. On a Sunday afternoon in 1955, they played a show with Eddy Arnold in Memphis. Afterwards, a blonde, courteous young man, wearing a pink shirt and black pants, approached them and told them that if he ever got a recording contract, he wanted them to sing back-up for him. Stoker said he didn’t think much about it at the time; people often did that and continue to do so today. On Jan. 11, 1956, Chet Atkins called Stoker to do a session with a new singer that Atkins said probably wouldn’t be around very long. It was the same young man that had approached them that day in Memphis—Elvis. RCA had just signed The Speer Family and Stoker, along with Ben and Brock Speer, sang back-up for "I Was the One," the first recording session Elvis had ever done with vocal background. In April, they were called upon again to sing back-up for Elvis in Nashville.

"The greatest thing that ever happened was when Elvis asked us to work," Stoker said. Elvis insisted that The Jordanaires’ name be placed on the record labels, and the recognition they received opened doors to other opportunities. "Elvis opened the door for everybody," Stoker said. "You could hardly find a guitar picker anywhere in those days. Now there is one on every corner. Elvis has inspired the world to sing and play." The Jordanaires ended their recording relationship with Elvis when he began to perform in Las Vegas. Stoker said that two shows a night were too hard for anyone to do. Elvis replaced The Jordanaires with The Imperials, who were later replaced by J. D. Sumner and The Stamps Quartet. According to Stoker, Sumner and The Stamps were about to quit when Elvis died. "I’ve always felt that two shows a night is what killed him," Stoker said. He believes the rigid schedule prompted Elvis to become more dependent upon prescription drugs.

Those who know Stoker are quick to smile and speak kindly of this humble, gracious man. Perhaps Todd Morgan, the director of media and creative development at Elvis Presley Enterprises, describes him best. "Anyone who thinks Dick Clark is the eternal teenager of show business has never met Gordon Stoker," he wrote. "His energy and passion for life and work and family and friends is boundless. He’s always got something going on. The only thing he has at the ready more often than music is humor. Any conversation with Gordon always involves a good laugh." Not a name-dropper nor a snob, just a kindhearted gentleman blessed with enormous talent. Weakley Countians can be proud to call him their own.

EIN thanks Pam Harris for her contribution. You can also check out the The Jordanaires website at www.jordanaires.net Copyright Elvis Information Network 2006. Do not re-publish this interview without permission. Click to comment on this interview

|

|