"Green

Carpet Ceilings: The Textile Art of Elvis Presley"

by

Mark Campbell

‘Human life is aesthetic for Freud in so far as it is all

about intense bodily sensations and baroque imaginings, inherently

significatory and symbolic, inseparable from figure and fantasy.

The aesthetic is what we live by; but for Freud this is at

least as much catastrophe as triumph.’ [‘The Name of the Father:

Sigmund Freud,’ in Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic,

(London: Blackwell, 1990), p. 262.]

|

‘I

love the fake, as long as it looks real I’ll go for

it.’ [Liberace, as quoted in Karal Ann Marling, Graceland:

Going Home with Elvis, (Cambridge: Harvard University

Press, 1996), p. 197.]

Evidently,

Joni Mabe, a regionally celebrated sculptor from Athens,

Georgia, owns one of Elvis Presley’s toenail clippings.

This revered artefact was discovered by Mabe during

a tour of Graceland – Presley’s Southern–Antebellum

style mansion in Memphis, Tennessee – buried amongst

the long synthetic fibres of the shag–pile carpet engulfing

the mansion’s private den – better known as the ‘Jungle

Room.’

|

|

This

clipping, now displayed amongst the Elvis whisky decanters,

collectors’ plates, costumes, lamps, clocks, watches, bedspreads,

pillows, ashtrays, bedroom slippers, towels, knives, cologne,

worn shoestrings, and generous vials of the King’s sweat,

forms the mythic centrepiece of Mabe’s tribute installation

sculpture. Variously known as The Elvis Room, or Joni Mabe’s

Travelling Panoramic Encyclopedia of Everything Elvis, this

mobile ‘cabinet of curiosities,’ veering precariously between

a self–described ‘high–brow level of Art’ and an indescribable

level of trailer–home collectivism, began when the artist

stumbled across this objet d’art and started to make an informal

collection of her own ‘Elvis–objects’ in celebration of it.

As

Mabe has written of this fortuitous discovery: ‘This was the

first time that I had gone through the house and I wanted

to touch where Elvis had touched. I was touchin’ the walls.

I was in the Jungle Room and the rest of the tour went on

outside. I just bent down and wanted to touch where he had

walked and not where everybody else had walked. I just felt

something in one of the fibres of the green shag carpet and

picked it out and it was this toenail clipping.’ (1.) Mabe’s

initial sense of astonishment had been tempered by doubts

concerning the clippings authenticity and – accordingly –

it is now labelled in the Travelling Panoramic Encyclopedia

as the ‘Maybe–Elvis Toenail.’

It

is evident, however, that nothing of Mabe’s archaeology –

whether it is authentic or not – could be described as serendip–itous;

in actuality the notion that a disembodied Elvis still resides

in Graceland, amidst the fiberous depths of the Jungle Room’s

luxuriant shag–pile, is endemic to the architecture of the

mansion. Essential to the construction of this notion – and

of architecture itself – is the figure of the Carpet. Instead

of acting as a simple material that covers architecture, the

archetypal function of carpet – as the German architect and

critic Gottfried Semper theorised in 1851 – is to define architectural

space itself. Asserting the primalcy of a suspended carpet

as the origin of walled architecture (as enclosure), he stated

virulently: ‘wickerwork is the essence of the wall.’

Such

a working of the woven carpet divides space; literally creating

architecture, this construction was coincidental with – and

entirely dependent upon – the advent of textiles. The inter–weaving

of carpet surfaces to enclose space is viewed by Semper as

a ‘patterning’ of the world, the creation an ‘interior world.’

As

such, the covering of the carpet actively constructs the domestic,

and such a comforting interior is the source of a ‘lasting–pleasure’;

a comfort brought about through the establishment of order,

pattern, and unity in the space of the domestic. This ‘striving

towards a lasting pleasure,’ becomes for Semper, ‘as old as

the pleasure’ itself.(2.)

A

statement that is ambiguously suggestive of the direct correlation

between the ‘comfort’ of the carpeted surface and erotic pleasure,

a convergence which is less than subtly implied in the ‘bachelor–van’

aestheticism of the shag–piled floor – and ceiling – of Graceland’s

Jungle Room. However, the notion of ‘comfort,’ as Siegfried

Giedion has written of the continued evolution of the modern

interior, has been divorced from its original meaning: ‘the

word ‘comfort’ in its Latin origin meant to ‘strengthen,’

however ‘the West,’ following the eighteenth century, ‘identified

comfort with ‘convenience.’ Man shall order and control his

intimate surroundings so that they may yield him the utmost

ease.’ For Giedion it is this deliberate designing for ‘ease’

that ‘would have us fashion our furniture, choose our carpets,

contrive our lighting.’ (3.)

Through

a concentration on ‘interior comfort,’ as a construction of

the domestic (and by implication architecture), architecture

is inverted – turned inside out – and form itself is displaced.

Within such a contrivance, the interior is perverted through

this displacement of form and privileging of a sense of comfort.

Lost, it would seem, amidst the confused profusion of interior

furnishings and decoration, was ‘man’s instinct for quiet

surroundings and for the dignity of space.’ (4.)

What

is more, this undignified loss of architectural coherency

began with the archetypical element of the carpet. For Nickolaus

Pevsner, writing in Pioneers of Modern Design, an exemplar

of these transformations was a patent–velvet tapestry – a

suspended wall of carpet – that was exhibited in the 1851

World Exposition in London and on whose surface ‘the artificial

flowers on the machine–made carpet shine more gaudily than

they ever could in nature.’ (5.)

The

greater the extent to which the ‘natural sense of the material’

– which the object imitates – is obscured by the object’s

artificiality, the greater the illusion of that object’s relation

to nature has to be reinforced. The 5" shag–pile of the Jungle

Room is unnatural. Furnishing the Jungle Room with a lavish

and undeniable opulence, it is a covering – between the architecture

of the house and the body of inhabitant – that is utterly

useless, obsolete, absurd, and fatally anaesthetised. The

luxuriant shag–pile is sublimely artificial – even more so

than the faux–Hawaiian furnishings of the room – and is splendidly

formless (rather than form–giving).

In

actuality, the essential element of the carpet of the Jungle

Room – rather than defining space – is that it is de–forming

rather than forming. The sensuality of the shag–pile, its

tangible fuzziness, collapses the room’s inhabitant into the

comfort of the interior, eliding the distinction between the

two. To clarify that the carpet is used here – not as a functional

material, nor as a symbolic definition of space – but precisely

because of it’s obsolescence and elision of the distinction

between the house and it’s inhabitant, Elvis covered not only

the floor of the jungle room with shag, but the ceiling as

well (figure one).

In

one early instance, illustrated in a fashion spread taken

for a local Memphis newspaper in 1965, the distinction between

the very–public image of Elvis Presley, and the closely guarded

private interiority of Graceland, melded into one another;

beginning a ‘technicoloured’ dissolution that would reach

it’s apotheosis in the Jungle Room. For this shoot Elvis was

photographed wearing clothes that were costumes from Viva

Las Vegas, made with Ann–Margret two years earlier, in Graceland’s

recently refurnished living room.

These

‘sharp new clothes,’ and the maturing attitude they mirror,

audibly reflect these renovations. However, it is not only

the clothes, or his co–star, which have transformed from the

fictive world of celluloid into the real world of Elvis: ‘It

comes as no surprise, somehow, that an early version of the

chandelier in Elvis’s dining room may be glimpsed dangling

from the ceiling of the casino in Viva Las Vegas.’ The disjuncture

between the fictive and the real was always preciously expressed

in Graceland’s architecture, with either one collapsing back

onto the other; aware that a celebrated private interior –

however–unseen – was a necessary complement to the public

persona of celebrity, Elvis paid scrupulous attention to the

interiority of his mansion, collapsing the exposure of the

exterior perilously into the world of the interior.

The

necessity of continued renovation – of incessantly altering

the interior in an effort to reinvent the exterior – was manifest

in Graceland. Stasis was – literally – death. Accordingly,

Elvis was ‘forever fiddling with his house,’ as Alan Fortas

(a member of his entourage known as the ‘Memphis Mafia’) has

said, ‘Changing things. Elvis liked red and the bright technicolour

of the films.’ This reinvention was obsessive and Elvis’s

‘attitude towards [other’s] efforts to modify his house were

always edgy … Graceland [itself] was sacrosanct.’ Priscilla

Presley, who lived at Graceland for six years before she married

Elvis, recognised that he was the one who made the decisions

on colour and style, admitting, ‘All I did was to change the

drapes from season to season.’

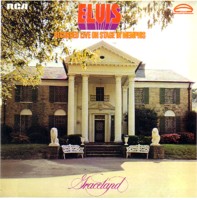

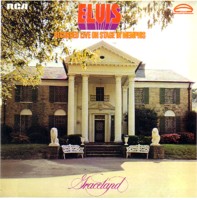

For

Elvis this activity was a form of Home–making, a mode of establishing

the (fictive) security of social order (figure two). Elvis

had always intended that the house would be a home for his

unified family, but with the death of his mother, Gladys Presley

(in 1958), what had been highly implausible, became physically

impossible. The strong identification that Elvis had with

Graceland stemmed from this unhealthy association with his

mother. ‘Gladys,’ as Priscilla Beaulieu Presley, Elvis’s only

wife wrote candidly in her autobiography, ‘was the love of

his life. She had died on August 14, 1958, at the age of forty–two,

of heart failure … He had expressed how deeply he loved and

missed her and how in many ways he dreaded returning to Graceland

without her there. It has been his gift to her, a private

estate that he’d purchased a year before she died.’

|

This

dread of returning to Graceland, mourning the loss of

it’s inhabitant fictions, continues to haunt it’s interiors.

These rooms retain a sense of emptiness; inspite of their

aesthetic loudness, they are quietened by a funereal absence.

This radical emptiness, repressed by the exterior, was

initially covered over by the exuberant expansion of these

facades. Elvis frequently altered the environment surrounding

Graceland, not merely because constant change alleviated

his terminal boredom, but because such an activity convinced

him that Graceland was an environment – which if not ever–changing

– was able to satiate his desires without leaving the

property (and eventually the house itself). |

In

order to accommodate these disparate activities (over the

two decades he owned Graceland), Elvis undertook the initial

planning for a variety of enclosed structures, all of which

– with the exception of the Trophy Room and the Raquetball

Court – were scrupulously planned, only to be abandoned for

the next project. These alterations variously included; an

underground shooting range to replace the old wooden shed

where target practice was held (following a neighbour’s complaints

of stray high–calibre munitions); a circular movie theatre;

an octagonal twin–level recording studio and music centre;

a snaking asphalted go–cart track; and a fully–operational

helicopter pad and hanger.

The

only permanent structure built was the Raquetball court; the

prototype for a network of courts Elvis developed in a speculative

and financially–disastrous venture with his doctor George

Nichopoulis. Needless to say, a series of 70’s era Elvis Presley

Raquetball and Health Clubs didn’t eventuate, and the court

wasn’t used for many activities independent of its extensive

mini–bar and medical cabinet.

Clearly

none of these schemes were undertaken with studied consideration

and one notable incident illustrates the architectural impatience

of a bored Elvis (a shown in figures three – six). Deciding

‘that he didn’t like the looks of an old house located on

the grounds in back of the mansion,’ as Priscillia Presley

wrote, ‘Elvis took a long look at it, called his father and

told him to get a bulldozer over there right away and get

rid of it. When the bulldozer arrived, Elvis insisted that

he was going to do the local honours, convincing his father

– and the local fire and demolition departments – that he

could handle the job himself. Wearing his football helmet

and his big furry Eskimo coat, Elvis proceeded, his entourage

cheering him on, to bring it down and set it on fire.’ Even

at the controls of a bulldozer, Elvis needed to maintain an

appearance of control.

For

the few activities that Graceland couldn’t accommodate, he

would drive into Memphis and hire the full–sized equivalent

– like the Fairground Amusement park or the Rainbow Skating–Rink,

or any of the local movie theatres (insisting the concession

stand remain open). However one hobby did briefly outgrow

the confines of Graceland. In 1967 Elvis brought a 163 hectare

ranch in Mississippi, renaming it the ‘Circle–G’ (inventively

after his house), in order to provide space for his interest

in horseback riding after ‘the hobby had outgrown the pasture

at Graceland.’ However, suffering from the increasing financial

strains of sustaining this hobby – and feeling homesick for

his mansion (which was twenty minutes drive away) – Elvis

sold this property.

Moving

the horses back to Graceland, Elvis contented himself with

riding the exhaust–fogged ranges – alongside the six–lane

Elvis Presley Boulevard (figure seven) – of the front lawn.

The provision of an interior content (to the exterior legend)

found expression initially during the sixties renovations

of the Trophy Room. In the ‘Hall of Gold,’ amongst the film

costumes and hundreds of Gold albums – representing the more

than 800 million albums he had sold – Elvis was able to closet

himself away as another object among the emblems of his immortal

career. The effect of the trophy room, as Albert Goldman has

noted with due–incredulity, ‘is less that of a trophy case

than the display case of a trophy manufacturer.’

Originally

the shed had been constructed to allow Elvis and his entourage

to race expensive toy slot–cars around a giant track. An indulgence,

which like several others, had grown from a Xmas gift into

something grander and – like the majority of Elvis’s hobbies

– was a distraction from tedium which soon became fatuous

itself. The empty shed offered him a large space to house

the records, clothes and momentos compiled throughout his

career. ‘Elvis never allowed anything to be cast out of Graceland,’

as Albert Goldman acerbicly noted, ‘except for human beings.

Once an object, no matter how trivial, came into his possession,

it remained with him for the rest of his life.’

It

is no coincidence that after their spontaneous wedding and

reception in the banquet room of the Las Vegas Hilton, Priscilla

and Elvis returned for a second ceremony, including extended

family and hangers–on, staged in the Trophy Room. In the midst

of his career trophies Elvis proudly presented his new bride,

an irony which wasn’t lost on the furious bride herself. An

ordered domestic interior was regime and as Priscillia, who

eventually resisted the petrification of being turned into

an object in Graceland, observed: ‘Elvis Presley created his

own world; only in his own environment did he feel secure,

comfortable and protected. A genuine camaraderie was created

at Graceland.’ However such an environment, despite it’s apparent

comfort, is nothing other than the temporary redecoration

of an illusion. What requires such a degree of interest in

the preservation of this fiction, as Susan Buck–Morss has

written, is the individual’s naive belief that they can be

created – and perpetually re–created – out of the inventive

material of their own imagination. Such a delusion of ‘auto–genesis’

maintains a ‘narcissistic illusion of total control.’ (6.)

Graceland

was sacrosanct for Elvis Presley and the external maintenance

of an illusion of total control over it’s exterior and interior

contents – as illustrated in Priscilla’s lacquered makeup

and fantastically unstable Sixties Beehive – was essential

(figure eight). However if Graceland is a fiction, one maintained

for the waning interest of its Regent, then it was an external

and hallucinatory one. As Priscilla recalled nostalgically

of her first arrival at the white mansion, as she was chauffeured

melodramatically up the driveway in an open–top Cadillac:

‘Graceland was everything that Elvis had said it would be.

The

front lawn was adorned with a nativity scene and the white

columns of the mansion were ablaze with holiday lights. It

was one of the most beautiful sights I’d ever laid eyes on.’

If the beauty of its exterior was virtually unimaginable,

then the possibilities of interiors were for the still–virginal

Priscilla, intoxicating (figure nine). Graceland was a seductive

interior which was not only bereft of the moral instruction

of fairytales, but of any tangible content whatsoever. As

Siegfried Giedion has written, although not admittedly of

Graceland, the agency of the interior decorator is the production

of artifice: the work of one who through the ‘embellishment

of furniture and artistic hangings, sets up a fairyland to

enchant the drabness.’ (7.)

This

charming of the mundane is the attempt to cover–over the inevitable

return of a domesticated boredom, and it was with the historic

emergence of the decorated private room, painstakingly arranged

with lavish coverings and plush furnishings, that the ‘devaluation

of space’ began. As the room’s decor subsumed the architecture

housing it, an un–easy tension was created between the contents

of the room and their container. While the opulent coverings

of the carpet attempted to cover over this dis–ease, the furniture

becomes merely a means to fill the room.

Apparently,

the furnishings of the Jungle Room – which seems to express

an incoherent faux–Hawaii beach party theme – resulted from

an impatient 25 minute redecorating spree at McDonald’s Furniture

store in Memphis in 1974, during which Elvis brought the entire

shop display and relocated it to the old sun porch in Graceland.

There it complemented an existing fake brick waterfall (vaguely

reminiscent of the haute–decor living room of Elvis’s wealthy

parents in Blue Hawaii), illuminated by an idiosyncratic series

of fairy–lights, along with the luxuriant lurid green shag–pile

carpet which already covered the floor – and ceiling – of

the room. However this room, despite it’s opulence, is emptied

out – of not only any tangible content, but of space itself.

‘Space itself doesn’t enter the interior, it is only a boundary.’

(8.)

The

contents of the interior are a ‘mere decoration’ and as one

commentator has written, they are ‘alienated from the purposes

they represent … engendered solely by the isolated apartment

that is created in the first place by their juxtaposition.’

(9.)

The

realm of the interior is created through the juxtaposition

of these objects, however it remains – paradoxically – empty;

literally without space. Conceived in such a manner the interior

is a mirror, reflecting the inhabitant who dwells – nestled

– within it. This self–reflection of the inhabitant appears

to be echoed by not only the underlying desire, but the very

materiality of Graceland’s architecture; juxtaposing the formlessness

of the shag–pile carpet are the sharpened reflections of the

mirrors which are spread throughout Graceland. This use of

mirrors had an interesting history, originating in 1960, when

Elvis relocated to Hollywood to resume his film career, following

the conclusion of his military service, where he had already

brought a house at 565 Perugia Way in Bel Air.

Constructed

in a faux–Oriental style with an elaborate garden and waterfall,

this circular mansion was perfect for the self–indulgences

of stardom and had required only minimal redecoration, mainly

consisting of the installation of white shag–piling, pool

tables and a jukebox. However, one very significant alteration

was made: a two–way mirror would also be installed, to accommodate

Elvis’s growing attraction to voyeurism. This mirror was installed

in a hand–dug crawl–space, running alongside the pool–house,

overlooking changing guests.

However

the physical discomfort of using it impelled Elvis to relocate

it to the interior of the house, renovating the internal layout

to construct a wall between one of the bedrooms and a small

concealed room with this viewing glass. From the privacy of

this closet, Elvis would watch the sexual antics he encouraged

between members of his entourage and unsuspecting female guests.

However, Elvis became frustrated by the technical crudity

of the perennially steaming mirror–wall, and his inability

to orchestrate the performance from behind it, and soon began

deploying a primitive video camera.

The

technological detachment of this device allowed Elvis to tape

his favourite scenarios, then endlessly replay them. When

Elvis eventually moved out of Perugia Way his nostalgic attachment

to this mirror–wall compelled him to freight it to Graceland,

where it was too large to ever be installed, remaining stored

in the attic amongst other unknown treasures. In the extensive

renovations to Graceland in 1974, several other mirrors or

highly reflective surfaces were installed throughout a number

of the mansion’s interiors. A continued attention to detail

meant materials were installed in strange locations; small

swatches of red shag were used as cabinetry infill panels

on the first floor and mirrors were installed on the ceilings

of stairs and a basement room, in which Elvis ‘could lie back

in splendid repose and upon a bank of velvet cushions and,

from underneath one heavy, half–closed eyelid, watch himself.’

(10.)

The

preponderance of reflective surfaces is never more apparent

than in the interiors of this basement room: the television

room (figure ten). Designed and executed in 1974 by the Memphis

decorator Bill Eubanks, the blue–and–white television room

– with its mirrored fireplace surrounds, podiums, tables,

plant–pots and ceiling – is possibly the most breathtaking

of all the mansion’s rooms open to public view. The deco–inspired

op–art super–graphic motif, from which the room takes its

cue, spews out a potentially–nauseating profusion of forms

and colours, surfaces and reflections. And nestled into the

plush blue velvet and yellow formica rear wall, between the

stereophonic hi–fi system and the primitive video, are the

rooms three small television sets. The idea of watching several

televisions originated in a visit to the Whitehouse of President

Lyndon Johnson, who had installed 3 sets to simultaneously

watch the network news broadcasts. Elvis, in turn, watched

a ‘limited variety of shows ranging from sporting events to

sitcoms.’

Strangely

the main orientation of the room turns toward the formal fireplace,

away from the television sets, and despite the padding of

the custom designed and upholstered sofa and ottomans, the

surfaces of the television room remain uncomfortably hard.

As Karal Ann Marling has written of the formality of this

room – coupled with adjoining games room (also designed by

Eubanks) – ‘form a unity based on the range of possibilities

in high end decor of the 1970’s … the studied disposition

of parts suggests public or quasi–public spaces, like cocktail

lounges and hotel rooms these spaces remain impersonal and

lifeless.’

The

unyielding hardness of these furnishings and coverings is

reflected – literally – in the uncomfortable profusion of

images flickering across the television room. Elvis rarely

relaxed into watching television here, consigning to use it

as a more formal entertainment room (due to the exceedingly

generous size of its built–in bar). In contrast, as Lynn Spigel

has written, ‘the ideal home theater was precisely ‘the room’

which one need never leave, a perfectly controlled environment

of wall–to–wall mechanised pleasures.’ (11.)

The ‘ideal home theater’ of Graceland was a room – resplendent

with mechanical pleasures – in which the inhabitant was more

often likelier to be the protagonist than the spectator. What

is more, it is within the inescapable comfort of the Jungle

Room that the most–domesticated incidents of his pathological

behaviour took place: the infamous execution of television

sets during of the 1970’s. While Elvis had undoubtably shot–out

a number of other television sets in a similar manner, most

probably in the penthouse suite of the Las Vegas Hilton, where

he regularly stayed while performing and habitually shot at

the imitation crystal chandeliers, the Jungle Room remains

the site of the definitive – undeniable – incident.

As

the story goes – late one afternoon in 1974, Elvis Presley

was sitting in his faux–Hawaiian driftwood throne breakfasting

while watching television. Finding a Robert Goulet entertainment

special particularly objectionable, and pausing only briefly

to put down a forkful of crispy bacon, Elvis – barefoot on

his dangerously lurid 5" green shag–pile carpet – reached

for his even more dangerously loaded and ever–present silver

plated pearl–handled .357 Magnum to register his ratings disapproval,

reputedly whilst muttering under his breath and through a

mouth of half–chewed bacon, ‘get that shit out of my house.’

Considering

that he had withdrawn so deliberately from a world exterior

to the walls of Graceland, it is pertinent that Elvis not

only treated his furniture with such contempt but choose to

sever so violently the only connection he had with the outside

world. That he would splutter ‘get that shit out of my house,’

is telling and rather ironic considering Elvis Presley died

attempting to do precisely that, (sufferering a massive heart–attack‘whilst

straining at stool’ to quote the Memphis Coroner’s report).

Of

course his father Vernon, or one of the boys, just wheeled

in another television between mouthfuls and, assumedly, got

additional ammunition if required. This metaphoric self–blinding

is further exaggerated given that Elvis was physically losing

his sight. In March 1971, he had complained of acute pain

and inflammation in his left eye during a difficult recording

session in Nashville and had been rushed to a local hospital.

There he was diagnosed with glaucoma in both eyes, a diagnosis

which was subsequently confirmed by his private physician,

Dr Nichopoulos.

This

disease had originated in years of chronic drug–abuse and

continued to bother him for the remaining years of his life,

ironically the anti–glaucoma medication contributing to his

narcotic addiction. Therefore it may be suggested that another

reason for the constantly draped windows and extravagant dark

glasses of the Seventies, aside from the obvious allure of

their costumed eccentricity, was a growing sensitivity to

light. A sensitivity – however conducive to his nocturnal

lifestyle – that forced Elvis to diligently avoid bright,

even natural, light. Only an insanely heightened sense of

vanity prevented him from wearing sunglasses on–stage, believing

that the audience made eye contact during the performance,

oblivious to the fact that these eyes were regularly obscured

by a reddened veil of drug abuse.

Given

that Elvis was physically blinded, and metaphorically short–sighted

(through the severance of his televisual ‘window’), it is

significant that he preferred the tactile environment of the

Jungle Room over the infinite self–reflections of the Television

or Trophy rooms. Instead of the mansion’s interiors acting

as a mirror to reflect it’s inhabitant, there is no visible

reflection on these polished surfaces whatsovever – it is

in the merging between the 5" shag–pile carpeting of the Jungle

Room and an equally blurred Elvis that is the point at which

‘he was Graceland, Graceland was Elvis.’ Elvis didn’t need

– nor did he want – to see himself in Graceland, as some commentators

have suggested, rather he wanted to feel himself inside of

Graceland.

And

it is evident that it was only within the privacy of his den

that he felt such a tangible sense of comfort. Yet ‘there

is no indication that Elvis meant the Jungle Room to be preserved

intact for posterity,’ as Marling has written. However with

Elvis’ death in the en suite bathroom on the 16th August 1977,

that is exactly what happened to the most personally encoded

of the mansion’s rooms. At this moment Graceland shifted from

being a private house to a museum – or perhaps more appropriately

– to a mausoleum. In her chapter on the furnishing of the

Den, ‘Elvis Exoticism: the Jungle Room, from her wonderful

book Graceland: Going Home with Elvis, Karel Ann Marling defines

the Jungle Room as kitsch, writing; ‘lets face it … the Jungle

Room is stunningly, staggeringly, tacky.’

This

is a strange disjuncture given that Marling had been empathetic

in not reducing Elvis to a caricature via the aesthetic sensibilities

of ‘bad taste.’ And given that even a sympathetic critic such

as Marling should flounder – undisguisably nauseated – in

the interior of the jungle room is significant. As the ‘tasteful’

architect, Vittorio Gregotti has written of such a floundering,

‘Nothing is more ludicrous than the retreat … from the concept

of design to one of ‘furnishing’ … [or] … the concept of the

‘anti–house’ which is conceived from the inside and demonstrates

at best a lack of cohesion between the interior and the exterior

or at worst a deplorable falsity of architectural conception.’

(12.)

An

elision between the exterior and the interior of architecture

which is for Gregotti the virtually unimaginable conception

of the ‘anti–house.’ Such a discomfort with the decor of the

Jungle Room – a ‘deplorable falsity of architectural conception’

– is not atypical; indeed is it the source of its nomenclature:

‘The Den became the Jungle Room when the house tours began

because the decor embarrassed the staff. Giving it a name

made the excruciating lava–lamp, semi–hipness of the place

seem meaningful.’ (13.)

At

the point that the private interior of the house became openly

public, it’s interior – and all it’s vestiges – were subsumed

by the ‘exterior’ myth that surrounded it’s inhabitant. As

Marling herself notes: ‘The Graceland tour is careful to avoid

anecdotes that might lend support to the unbeliever’s mental

image of a bulging besotted King who was fatally out of control

or dying in his very excessiveness.’

In

contrast to the fatal excessiveness of the Jungle Room, Marling

places the deliberate architectural campiness of Elvis’s friend,

Liberace, whose ‘tastes’ are seen as a form of ‘connoisseurship,’

an ironic indulgence in the aesthetic sensibilities of bad

taste and obsolescence. ‘I love the fake,’ as Liberace told

an interviewer, ‘As long as it looks real, I’ll go for it.’

Marling’s opposing of the Jungle Room with Liberace’s various

Las Vegas mansions agrees with a conventional definition of

camp as precisely a ‘cultivated bad taste – as a form of superior

refinement.’ Or, as Susan Sontag puts it simply, ‘it is beautiful

because it is ugly.’ The Jungle Room, rather than being an

interesting – or defining – moment in the architecture of

Graceland, is reduced to being read as mere aesthetic inadequacy,

just plain bad taste: ‘There is no similar irony in Elvis’s

Krakatoa-style den. Only a rush of pleasure enhanced by the

awareness that there were more jokes to come, more wacky stuff

from Donald’s to buy some day, more Saturday matinee fantasies

to be lived out in the privacy of Graceland.’

For

Marling the decoration of the Den is an ‘act of serial novelty,’

an impermanent and ever changing joke to be renewed as soon

as its architectural punchline became worn-out. The interior

of the Jungle Room was never meant to be permanent and ‘Elvis

had the great misfortune to die before his den.’ While the

relationship between the ‘serial novelty’ of the joke and

a notion of the aesthetic may not at first appear to be an

obvious one, it elicits a tensing out here in order to provide

an alternative to reducing the Jungle Room’s interior to a

dismissive reading as merely the ‘bad taste’ of an uncultivated

aesthetic sensibility.

Aesthetics

was originally conceived of as a discourse of the body. And

in this original form it refers, not to the artistic, but

(as Terry Eagleton has written) to the ‘whole region of human

perception and sensation, in contrast to the more rarefied

domain of conceptual thought. The distinction which the term

‘aesthetic’ initially enforces in the mid-eighteenth century

is not one between ‘art’ and ‘life,’ but between the material

and the immaterial: between things and thoughts, sensations

and ideas.’ (14.)

Thought

of in this manner the aesthetic distinguishes between the

material and the immaterial (form and content). Writing on

the restorative psychical action of humour, in a paper appropriately

titled ‘Humour,’ Sigmund Freud regarded humour as ‘a kind

of triumph of narcissism, whereby the ego refuses to be distressed

by the provocations of reality in a victorious assertion of

its invulnerability. Humour transmutes a threatening world

into an occasion for pleasure.’ As such, the agency of humour

transfers the reality into something less serious and assimilable

into the experience of the subject as pleasurable – this is

the classic articulation of the ‘pleasure-principle,’ which

actively transfers the unpleasureable into the pleasurable.

To

the extent that humour operates, through this narcissistic

transference, in the provision of a technicoloured version

of reality – within which the subject is inviolate – humour

is sublime: ‘It resembles nothing as much as the classical

sublime, which similarly permits us to reap gratification

from our senses of imperviousness to the terrors around us.’

The humorous can be tangibly aesthetic then – as the aesthetic

is the mediation between the material and the immaterial,

the sensation and the idea, the real and the fictive.

Moreover,

this liminal oscillation between these states is not only

a condition of aesthetic existence – but is in itself traumatic.

‘Human life is aesthetic for Freud in so far as it is all

about intense bodily sensations and baroque imaginings, inherently

significatory and symbolic, inseparable from figure and fantasy,’

as Eagleton writes, but as he adds cautiously, ‘for Freud

this is at least as much catastrophe as triumph.’

An

aestheticised insulation from trauma, as Freud famously stated,

is more fundamental than the positive reception of experience:

‘Protection against stimuli is an almost more important function

for the living organism than the reception of stimuli.’ Such

a form of protection, literally a Self-protection, mediating

between pleasure and displeasure, comfort and discomfort,

takes place on the site of the body.

The

pleasure principle constructs itself as a shield at the extremities

of the body in its attempt to shield the subject from the

potentially fatal excess of reception. The subject, ‘suspended

in the middle of an external world charged with ‘the most

powerful energies,’ would be mortally injured if it wasn’t

protected form these forces by a protective layer.’ Elvis’s

need to protect himself from a physical exteriority had increased

dramatically during the drug-fuelled paranoia of the Seventies,

as is graphically illustrated in the Jumpsuits worn to perform

in during the final years of his life (not to mention his

insistence on ‘packing heat’).

The

evolution of these costumes, as at least one commentator has

pointed out, had exceeded the practical demands of performance

– transforming into a kind of rampant symbolism. From the

arguably pragmatic leathers of the 68’ Singer-Special, they

evolved into the classic jumpsuits of the early Seventies,

clothes which not only had names, but personas: like the Mad

Tiger, the Pre-Historic Bird, the Mexican Sundial, and the

most famous of all – worn only during the 73’ Satellite Special

– the American Eagle. Resplendent – with cape unfolded to

ascend to the heavens – the jewelled, studded, fringed, and

laced ‘jumpsuit Elvis is a different creature, the Vegas Elvis,

a legend armoured in a caraplace of sheer, radiant glory.’

These were more than clothes, they were a liturgy, ‘Elvis

the icon was cosmic, mysterious, all-American, untouchable.’

(15.)

This

ornamented invulnerability was an attempt to shield the self

from the strains of being itself. As Elvis had entered his

final decade, his personal fiction had became public property;

‘now the entire world was urging him to live his fantasy.

He could now celebrate a career that included an evolution

from a teen idol to movie star to worldwide cultural phenomena.’

(16.)

As

his personal life imploded around him, Elvis Presley recorded

a concert performance at the Honolulu International Center

Arena on January 16, 1973: an event, which as his official

Graceland biography succinctly puts it, was ‘the pinnacle

of his superstardom.’ Broadcast in over forty countries, the

‘Elvis: Aloha from Hawaii – Via Satellite’ television special

(made to raise funds for the USS Arizona War Memorial), is

the most viewed event in human history.

Surpassing

the Apollo 11 Moon landing, and was eventually seen by almost

one and a half billion people (at the time over half of the

world’s population). As a result of the enormous publicity

this engendered, by the time of his death – only four years

later – Elvis Presley had become the most photographed human

figure in history. An image bearing his likeness had become

the most recognisable representation around the globe.

This

phenomenal success, as he himself was acutely aware, lay in

this reduction to an image; a serial reproduction. As Elvis

himself stated, ‘the image is one thing and the human being

is another – it’s very hard to live up to being an image.’

Following such over-exposure there was no need for him ever

to perform again, or – because he was available in so many

different representations – even to exist at all. Furthermore,

as so many contemporaries have noted, when he toured subsequently

it was purely for financial reasons and Elvis had degenerated

– or merely completed the natural evolution – into self-parody.

Describing

a narcotically-hazed, slurred and generally incoherent performance

in Houston’s Astrodome during August 1976, during which the

performer forgot the lyrics to even his seventeen year-old

standards, one reviewer wrote, ‘attending an Elvis Presley

concert these days is like making a disappointing visit to

a national shrine.’

This

monumentalisation underscored the futility of continued renovations;

within the proliferation of impersonators, each with a given

time and era, Elvis had been petrified. This confrontation

between imitations which were unable to recognise themselves

(as figure eleven graphically illustrates) elides the distinction

between the original and it’s serial imitations, drawing a

pained attention to the redundancy of the original. This overwhelming

of the individual by the serial – a loss of the interior to

an exterior – is an incomprehensible shock to the system.

If

the body is the site of the ego (as Freud postulated) – then

the protective function of this body, the ‘synaesthetic system,’

breaks down with this overcoming. The attempts to neutralise

this shock are numbing. ‘The cognitive system of synaesthetics

has become one of anaesthetics,’ as Susan Buck-Morss has written,

and ‘drug addiction is characteristic of modernity. It is

the correlate and counterpart of shock.’

It

isn’t necessary to over-state the well known extent of Elvis

Presley’s drug abuse, suffice to say he ‘had become a connoisseur

of recreational drugs and of the fine nuances of their euphoric

affect’ and consumed narcotics with the physiological appettite

of a small elephant. Such an appreciation of sensory-deprivation

does illustrate the escalating extent to which Elvis felt

(tangibly) affected by his image as the King and his inability

to numb the sensations of boredom and exhaustion.

The

correlate between the domestic site of drug-addiction and

an unsatiated addiction for the domestic is found in the renovations

of hotel rooms during the final concert years, renovations

which were meant to imitate Graceland. This dependency on

a ‘home away from home,’ coupled with the desire of Elvis’s

Manager – Colonel Tom Parker – for unmitigated concealment,

nearly had fatal consequences. In one virtually incomprehensible

incident Elvis’s first overdose (of many) took place ‘behind

the closed and guarded doors of the Las Vegas Hilton Suite

361’ on February 19, 1973.

Fearing

the disastrous implications of a public scandal, a comatose

King was left to recuperate amidst the luxury of the penthouse

suite with a temporary hospital constructed around the bed.

‘If it had been anyone but Elvis Presley,’ as Peter Harry

Brown dramatically described the scene, ‘an ambulance team

would already have been en route to the Hilton. But Newman

and Esposito [two prominent members of the entourage] were

charged by Colonel Tom Parker with preventing just such a

scandal. So they did the next best thing: they transported

medical and oxygen equipment into the suite and built an intensive

care unit around the silk-sheeted bed.’

On

tour these hotel rooms were arranged with exacting instructions

to duplicate the master suite at Graceland. All the furnishings

were laid out in the same configuration and the windows –

which were already concealed behind newly hung heavy-velvet

drape – were sealed with insulation foil and duct-tape. In

such an environment it was impossible to ever ascertain what

time of day it was, or even whether it was day or night, and

in such an artificial environment it was easy to imagine that

the surroundings were Graceland. Elvis faded further and further

into Graceland, eventually venturing outside infrequently.

With

an escalating drug consumption and the loss of any reality

external to the fictive world of Graceland, it can be argued

that – aside from the ever-briefer moments he was on stage

performing – an anaesthetised Elvis Presley never ventured

outside Graceland. The quiet resignation of this final return

to the mansion’s emptied rooms is apparent in the decor of

the Jungle Room and the formless artificiality of it’s shag-pile.

The synaesthetic system of the body has broken down, dissolved

into the comfort of the surfaces that surround it; no longer

mediating between the pleasurable and the un-pleasurable,

or perhaps no longer wishing to distinguish between the fictive

and the real.

The

architecture of this room marks the final – vacated – moment

of it’s inhabitation: a last attempt to give it a content

which had become lost, like a stray toenail clipping, amidst

the long synthetic fibers of the shag-pile. The final moments

of Elvis’s recording career took place in the Jungle Room.

From its inauspicious beginnings in the bleak hardness of

the acoustically tiled walls and stained linoleum floors of

Suns Studio’s cramped recording room, the recording career

of the King – who had sold enough records to stretch around

the globe twice – dissolved into the formlessness of the den’s

carpet: a dissolute formlessness apparent in the album recorded

there.

In

February, 1976, his final studio album was recorded at Graceland,

as a result of his refusal to leave the house. As one commentator

has described this bizarre scene: ‘The musician’s equipment

had to be lowered in through the windows of the Jungle Room

den. But after everyone had assembled, Elvis refused to come

downstairs. He said he was sick. Over the week that followed,

Presley eventually recorded a dozen songs. As Elvis put it,

that night, to producer Felton Jarvis, ‘I’m so tired.’ ‘You

need a rest,’ replied Jarvis. ‘That’s not what I mean,’ said

Elvis wearily. ‘I mean, I’m just so tired of being Elvis Presley.’

(17.)

This

sense of fatigue was indefeasible and as the Chicago Sun-Times

eulogised so succinctly in their obituary of August 18th 1977:

‘Decades of being ‘The King’ had affected him. The body failed

the test of the reign. Apparently the spirit flagged too.

Then the energy – and thus so much of the talent.’ And, as

they concluded rather ungraciously, ‘At least the legend still

lives.’ As the obituarist obviously thought; not only was

the legend exhaustedly limping along without a body to bear

it – but it was itself emptied out, interior-less. On the

18th of August, 1977, an inert Elvis Aaron Presley lay in

a nine hundred pound casket, identical to the one he had buried

his beloved mother Gladys, in state barely inside Graceland’s

front door.

The

solid-copper casket lay underneath an elaborately cut crystal

chandelier (resembling a film prop), beside the stairs leading

mysteriously to the upstairs bathroom where Elvis – straining

under the pressure of being the King – had drawn his final

breath. That afternoon, the body of Elvis Presley was carried

through the entry of Graceland for the final time by members

of the Memphis Mafia and driven to the local cemetery to be

laid to rest beside his mother. Barely a month later, Vernon

Presley – fearing further attempts of grave-robbing after

two local men had been arrested at the graveside carrying

shovels – exhumed both bodies and brought them to their final

resting place, in the Garden of Contemplation beside the swimming

pool, in full view of Graceland – literally in the back yard.

Graceland

had exhumed the body of the King, drawing Elvis back into

the uneasily domesticated realm of the interior, assuring

they remain indivisible. It is difficult to think of one without

the other and – in thinking of one without the other – either

one is disembodied. If the impatient furnishing of the Jungle

Room is a joke – from a however deluded and unquestionably

naive sense of humour – then it is also the moment at which

the body of the King, exhausted from representing itself,

and the architecture of Graceland dissolve into one another.

If

it is a punchline which has indeed worn thin, as one commentator

has suggested, then its tragedy – which doesn’t preclude it

from being hilarious – is this tangible sense of exhaustion:

there are no more pranks, no more practical jokes, no more

reassuringly narcissistic assertions, to follow. Instead of

containing the lurid artificiality of the Jungle Room’s shag-pile

carpeting, and its contents, within the conveniences of ‘aesthetic

inadequacy’ – of being just ‘bad taste’ – perhaps we are left

laughing, however awkwardly, at the hollowness of the joke

itself.

Notes:

1.

Joni Mabe, ‘Everything Elvis,’ in John Chadwick ed., In Search

of Elvis: Music, Race, Art, Religion (Boulder: Westview, 1997),

p. 155.

2.

Gottfried Semper, ‘Style in the Technical Arts or Practical

Aesthetics,’ in The Four Elements of Architecture and Other

Writings, trans. Harry Francis Mallgrove and Wolfgang Herman

(New York: Cambridge UP, 1989), p. 235 (emphasis added).

3.

Siegfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command (New York:

W. W. Norton, 1969), p. 260.

4.

Ibid, p. 345.

5.

Nickolaus Pevsner, Pioneers of Modern Design: From William

Morris to Walter Gropius (Harmonsworth: Penguin, 1960), p.

41, as cited in, Christoph Asendorf, Batteries of Life: On

the History of Things and Their Perception in Modernity, trans.

Don Reneau (London: California UP, 1993), p. 125 (refer note

14, p. 232).

6.

Susan Buck–Morss, ‘Aesthetics and Anaesthetics,’ in, October

62, (Cambridge: MIT Press, Fall 1992), p. 8.

7.

Giedion, op cit, p. 365.

8.

Theodor W. Adorno, Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic,

trans. Robert Hullot–Keller, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press, 1989), p. 43.

9.

Ibid, p. 43.

10.

Karal Ann Marling, Graceland: Going Home with Elvis, (Cambridge

: Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 219.

11.

Lynn Spigel, ‘The Suburban Home Companion: Television and

the Neighbourhood Ideal in Postwar America,’ in Beatriz Colomina

ed., Sexuality and Space, (New York: Princeton Architectural

Press, 1992), p. 198.

12.

Vittorio Gregotti, ‘Kitsch and Architecture,’ in Gillo Dorfles

ed., Kitsch: The World of Bad Taste, (New York: Universe,

1969), p. 276.

13.

Marling, op cit, p. 192.

14.

Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic, (London: Blackwell,

1990), p. 13.

15.

Marling, op cit, p. 82–82.

16.

Whitmer, op cit, p. 274.

17.

Brown and Broeske, op cit, p. 400.

|

|